It is impossible to go a day at DHS without hearing some kind of music. Passing the band building, over someone’s Bluetooth speaker, leaking through someone’s wireless headphones… Whether we think about (or appreciate) it or not, it’s there. It’s been this way forever—since the Walkman, the Crosley radio, the phonograph, and long before then. Art is intrinsically programmed into the human mind and spirit, and by extension, so is music. Every culture since the dawn of time has some form of singing or instrumentation.

So, what is it? How can the Inuit Alaskans have something so closely in common with the Zulu? Why do we always come back to music?

“ARE YOU SOME KINDA’ HYPNOTIST??” – THE FLAMING LIPS

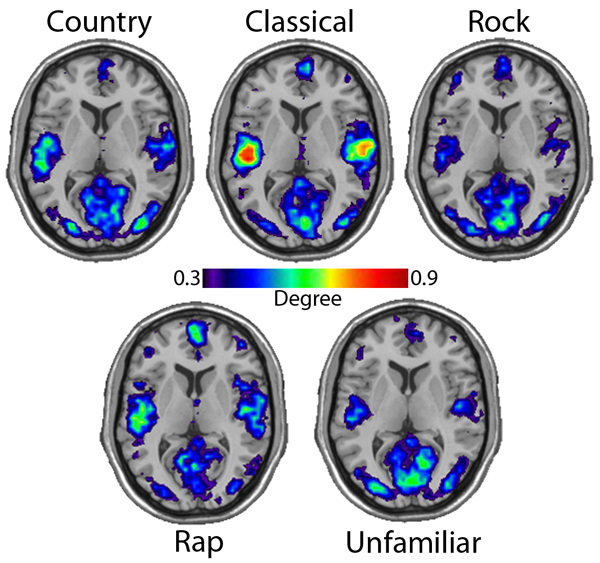

There are many scientific reasons for why we are drawn to music. For one, music triggers hormones like dopamine in our brains when we hear music (especially something familiar or associated with a certain memory), making the experience more intense and enjoyable. Music is so tied to emotion that even those with brain damage who could no longer recognize melody could accurately attach an emotion to a song.

Making music also has a significant effect on our emotions. Singing is possibly the most important—mothers who sing to their newborn babies can increase bonding and relieve symptoms of postpartum depression. When we sing, our brains release oxytocin and endorphins that make us feel good. Our anxiety is lowered, and confidence is boosted. It may motivate us, too, as an anonymous DHS student put it: “Music for me provides forward momentum. It pushes me to do new things and push my ability and understanding everyday.”

Meanwhile, learning an instrument has similar effects, and it can be a great coping mechanism or distraction. Being able to put our rough emotions into singing or making music turns the negative feelings into a piece of art. We may be able to appreciate all of our emotions more because of this, rather than throwing the emotion away or denouncing it as useless and harmful. After all, what great artist has had a perfectly happy life?

“DON’T TAKE ME BACK, IT WON’T BE THE SAME” – MIKE KROL

Just like Pavlov’s dog, we connect music to certain memories, time periods, emotions, people, and more. When you hear Toxic by Britney Spears, chances are you’re reminded of the early 2000s, through a grainy camera, and even what you were doing when you heard that song. It’s also why we remember information better if it’s presented to us in a song—think of the alphabet song, or the pi song, or one of those song parodies your history teacher showed you in middle school.

Music therapy has frequently been used by doctors and in studies to help patients with brain damage or dementia. Every timbre is so complex that the brain can place the time at which the sound was heard, and even patients with late-stage dementia are able to tap out or sing melodies from their early childhoods. Personalized music for each patient is thus most helpful; patients are most able to recall songs that are significant and personal to them.

Muscle memory also helps us maintain the ability to play an instrument we’ve learned despite not playing often anymore or suffering from memory loss. The most complicated music or instrument you play, the harder your brain has to work to do so. It involves heavy communication between all parts of the brain and body, especially for coordination-heavy instruments like drum set or piano.

“A MASK OF MY OWN FACE / I’D WEAR THAT” – LEMON DEMON

Music is vitally important to the formation of our identities. Especially today, for hyper-online teenagers, music appears in countless ways just within our phones. Many teens seek a sense of self in music, which is why we feel the need to attach certain labels to ourselves that not only denote what we listen to, but who we are. To some, these things are the same. “Swiftie” can mean just as much as your name, and your whole life journey. It lays out the soundtrack you have personally chosen for yourself, and that says a lot. When you’re upset, do you take solace in acoustic guitar? Or Limp Bizkit? Do you look for lyrics, or rhythm?

An artist is not just associated with their sound, aesthetic appeal, lyrics, and genre, but also their fans. By calling ourselves part of a fandom, we’re saying, “I don’t just like this—I’m a part of it.” We choose to engage with other fans and label ourselves accordingly.

For those still forming their identity, music can be a great comfort, and that inevitably leads to some connection between the two. Music is a culture, as is the chaotic devotion of BTS fans, and the cattiness of Nicki Minaj fans on Twitter. The connection between music and identity has gotten so intense that you can look at someone’s profile, see the label “boygenius stan” (stan meaning a hardcore fan, to be simple about it) and immediately form preconceived notions about them.

Some online users will block or avoid contact with certain users just because they are a self-proclaimed fan of something. This might be because a piece of music has been deemed problematic by the general public, or simply that what you’re into lets others know your standards. If you like something others think is mediocre, they might think less of your opinions on the subject. Your choice in music and what (or who) you associate with can define who you are, both to yourself and others. This is only reinforced by the fact that many genres of music are bound to styles of dress, speech, and even political ideology (see: punk, riot grrrl, etc.).

“YOU’RE THE ONLY FRIEND I NEED” – LORDE

As discussed in the last section, music and community are inseparable. Music fosters community, and often, communities create their own unique music. One of the big appeals of music is that it provides a community to belong to. Whether this is a counterculture like emo, a band, a fandom, or a sweaty crowd of people at a show, music is a breeding ground for bonding.

I can’t count how many times I’ve shared music as a means of getting close to someone. You offer them one of your earbuds, you make a playlist for them, you invite them to a concert—instant connection. Often, music elicits the memory of people, not just things or moments.

This also manifests when you’re the one playing the music. All the time spent with others on stage, on buses, and practicing music is time spent making memories. DHS senior Warrick Broecking says, “Lots of my friends are my friends because we bonded over music.” It also means dealing with the hardships of music-making together.

Sometimes a musical connection can be a parasocial relationship. We may find comfort in not just the music, but the person or people behind it, and start to feel like we know the artist personally. “She just gets it,” is something we’ve all probably heard countless times about popular artists who really speak to teenage emotions. It’s common practice to project our own experiences or emotions onto someone else’s works of art—it’s not always a bad thing, but it can be dangerous when we start to form ideas on who the artist is and what they’ve been through, despite us not knowing them at all.

A prime example of this is singer-songwriter Mitski. She’s exploded over the internet over the past few years mostly for her performance skills and highly emotional lyrics. Her songs usually deal with complex or upsetting topics, opening the door for people to relate to her lyrics with their personal experiences. If not that, we hear Mitski’s lyrics and assume she must have been through something horrible in order for her to write that. As a result, Mitski has been pegged as a “sad girl” artist, her entire discography flattened into this label. Her response to this in an interview by Crack Magazine was this: “The sad girl thing was reductive and tired, like, five, ten years ago, and it still is today. … Let’s retire the sad girl schtick.” And she’s right—Mitski’s music encompasses a wide range of stories and emotions, because she’s a complex artist. By reducing her entire body of work and personality to sadness, one loses out on all of the nuance in Mitski’s music and her person.

This thinking-we-know-things about artists extends into thinking they’re our best friends who just, like, get us. In response to people treating Mitski’s music like her personal diary, she said to Pitchfork, “Yes, it is personal. But that’s so gendered. There’s no feeling of, ‘Oh, maybe she’s a songwriter and she wrote this as a piece of art.’” This is similar to taking a storybook and projecting the plot and characters onto the author’s life; some things are not personal at all. Some things are inspired by a friend’s experience or a global event. Some things are just made-up.

Either way, our parasocial relationships reflect our connection to music in the most blatant and summative way. They prove our desire to connect with and through music—we want fandoms, we want to relate, and most of all we want to be understood.

“WE DON’T NEED NO THOUGHT CONTROL” – PINK FLOYD

Finally, music gives us an outlet to process the world around us. Art is made in the context and condition of the world at the time of its creation—in other words, current events impact what we make. This is also the case for visual art. Just take a look at Postmodernism, which emerged right after the Second World War, and was characterized by the stark realizations people were having that their governments and countries were not as morally good as people once thought. The world was ugly, full of atrocities, and artists couldn’t help but have this seep into their art. Postmodernism was thus focused on pop culture, abstraction, conflicting colors and styles, and making real things look unreal.

When it comes to music, the same phenomenon takes place. Bedroom pop, for example, exploded right around 2020 and in the years leading up to it, a genre revolving around independent artists making DIY music at home (hence the name). One of the biggest artists to come out of this was Clairo, who burst onto the scene with her single Pretty Girl. Her sound was obviously homemade, but people loved that, because it reflected an amount of relatability, authenticity, and the illusion that stardom was within close reach. Other examples include mxmtoon, girl in red, and Billie Eilish, all with millions of monthly Spotify listeners today.

This genre also has roots back to the 90s, where countercultures like grunge and a rejection of industry were the most prominent cultural themes. 1997 was the year that Fiona Apple gave her famous (infamous?) VMAs speech that pretty much sums up the youth’s attitude towards showbiz at the time: “This world is bulls—t.” Bedroom pop was an extension of this, with the addition of social media culture. In a world of increasingly fast-moving content and big corps all fighting for your last dollar, it makes perfect sense that young fans and artists would be desperate for something authentic. Platforms like YouTube were moving away from their traditional DIY mission and into something very corporate, and as usual, pop stardom seemed like a completely different planet for rising artists.

We gravitated so heavily toward bedroom pop because we as a culture were seeking something more honest, less commercial. It’s the same reason why these overnight stars like Clairo got so much flack for being supposed “industry plants.” Their worst crime was that they might have been produced by a major record label—proving that everything we wanted was separate from companies.

Marginalized groups were also seeking more and more representation, which could often not be achieved with a major record deal. Bedroom pop was a way to win public support and approval with not many resources at all. The message was this: anyone can make music. Interestingly, this era came right before what many would argue we are currently in: the “personal style” age of fashion, as we continue to seek authenticity and individuality.

There are plenty more examples of music reflecting our cultural landscape and giving us a chance to process it. See: jazz and blues emerging from African drumming and Voodoo rituals during and after the abolition of slavery. See also: psychedelic rock and the popularity of LSD in the 60s. Of course lyrics can be personal, but they’re also inseparable from current events and cultural developments.

“IT’S TIME TO EXIT WITH SOME GRACE” – HOP ALONG

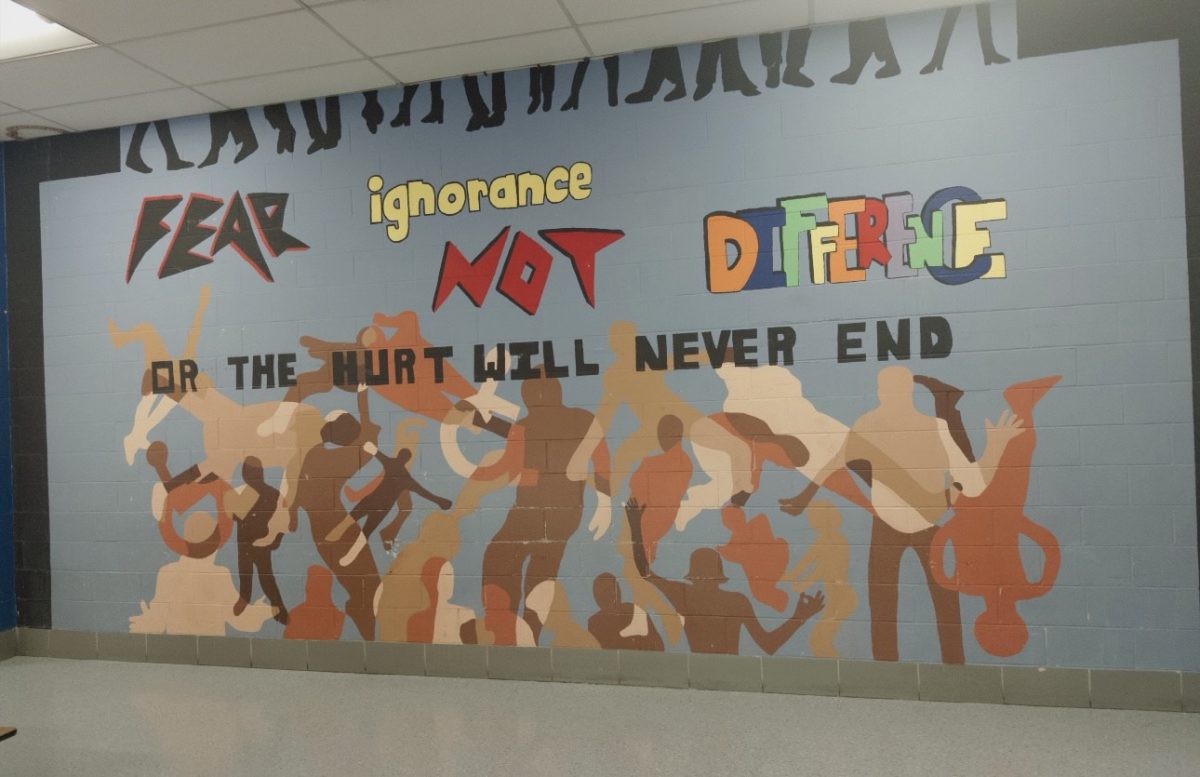

If music is unavoidable, we should at least come to appreciate it more than we do. Too often we are averse to certain artists or musical expressions because they are different. All types of music can provide what we’ve dissected today, and not one is superior or inferior to the other. In fact, it’s better to look at music as an interconnected web that ties all of us together. No genre is independent, and neither are we. We all manage to find each other along lyrics and between the notes.

This has been the first issue of the new musical column Sound Check with Jules. Tune in next week to hear about music history, review, recommendations, analysis, culture, and more!