To sing in Greek is to survive. It’s a very personal sentiment, and you can amend that by instead simply writing: to sing is to survive—but, in all fairness, this is a very personal article.

I lost most of my Greek family before I was born. Slowly, things dissolved, as my mother neglected to send me to Greek school or church, and I took my father’s last name. By middle school, I didn’t really know who I was fighting for.

Of course, there are influences I had been raised by and simply didn’t realize—like the simple sentences or phrases that I knew how to translate not because I had been taught but because I’d heard them since birth. I knew what έλα meant, I knew what σταμάτα meant, and I knew what a wooden spoon meant. I knew enough to get by, but visits with my grandmother were still plagued by her world warping to fit my (very American) world, not the other way around. For better or worse, anything Greek I knew were things I didn’t really understand. Things that I could feel, but not see. Then, I heard Eleftheria’s voice.

I rediscovered Greek music a few years ago with the song Είμαι Ερωτευμένος Με Τα Μάτια Σου (I’m in love with your eyes) by Eleftheria Arvanitaki. I was completely entranced by (or, you could say, ερωτευμένος) the fluttering bouzouki strings, the marching bass, the crowd clapping rhythmically, and the way Eleftheria’s voice sweetly commanded the room. I was overtaken by the hunger for more, and thus began my fall down the rabbit hole. I loved, more than anything, Alkistis Protopsalti, Arleta, Dimitri Galani… the list went on.

The sound of Greek singing satisfied something in me that nothing else did—it offered something English music could not. A lot of the heart of Greek music I was listening to is the πανηγύρι of it all. The crowd chanted along like they knew exactly what to do, the horns came from all directions, the drums beat wildly. My all-time favorite element was (and is) when singers used gamakas, like in Θα Σπασω Κουπες. Gamakas are “ornamented notes” in Sanskrit, and they’re very difficult to do justice through words, so here’s a video explaining a few. They’re heard in Indian Carnatic music, and pretty much all other cultures from the Bay of Bengal to the Mediterranean Sea.

I had heard them before, but they had been given a new life, a new celebration, perhaps because I understood them better now. In fact, Greek music made everything feel more in reach—if I couldn’t speak about Greece, I could sing. Lyrics were a source of learning new words, and rhythm filled in the gaps where nothing else made sense. Especially for me, for whom a straightforward family history was never in the cards. Who I was seemed to be a mystery; any past tragedy that might explain my present hurt was one I had to dig for.

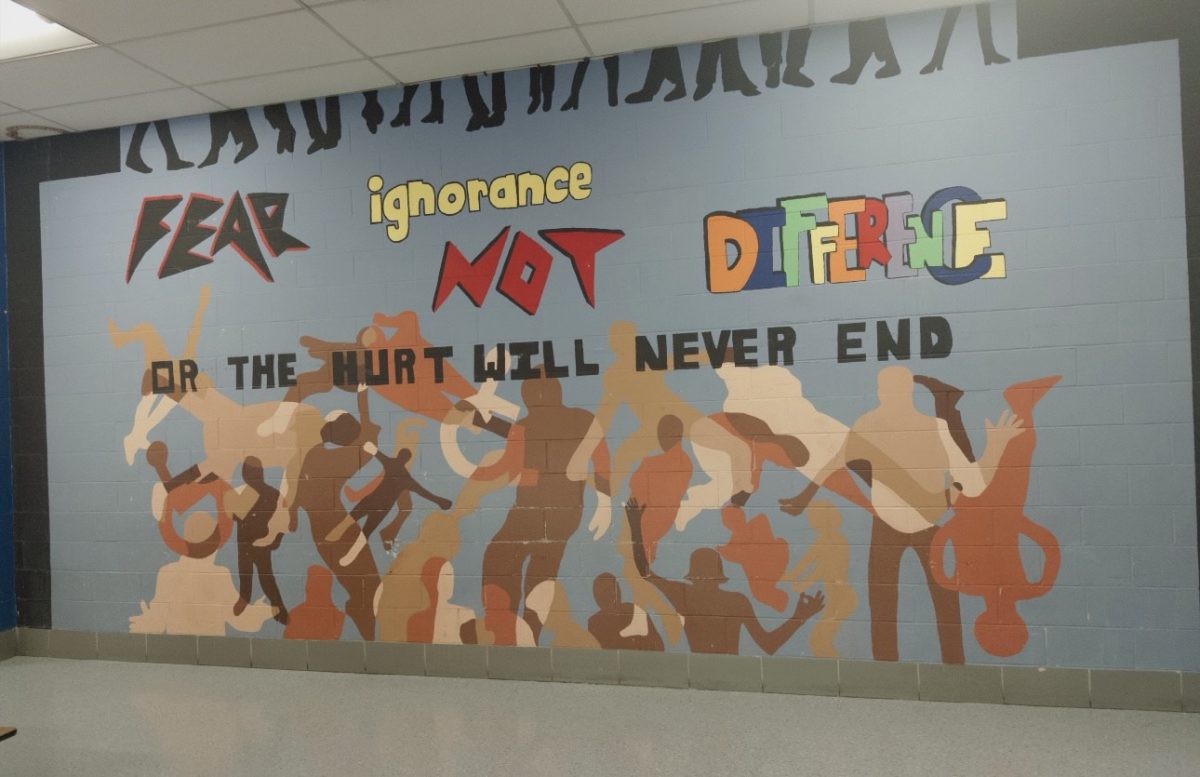

It was Odysseas Elytis who said “Greece fights like a small country; like a wronged one.” It’s true—Greece has been wronged time and time again, by the Romans, the Ottomans, the Germans, the Italians, Belgians, Brits… et cetera. But that’s not what stuck with me about this quote—it was the word “fight.”

Greece is a country built primarily on sheer will. It has had to resist and free and defend itself so many times, inside and outside. The fact that Greek history, language, and customs have survived so long is a testament in itself—especially during nearly 400 years of Ottoman rule, where Greeks were forcibly converted for the second major time in history, and “Turkified.” And yet, we still sing in Greek. We dance Greek. We fight Greek—small, wronged, but ever-present and inextinguishable. Suppression and oppression made us want freedom more.

Out in the diaspora, where I had found all of these songs, a similar theme rang true. Greeks in Canada and the US were no strangers to suppression, what with Hellenophobic riots and specific targeting from the Ku Klux Klan (yes, really). Greeks still spoke Greek, opened Greek restaurants, went to Greek Orthodox churches, sent their children to Greek school… of course, it wasn’t just that simple—being away from Greece and surrounded by growing white society made assimilation on some level inevitable. Many Greeks had to change their names for business and safety, while others left their faith or stopped speaking Greek entirely.

In other words, many were losing the Greek fight. When my lineage got to me, there was little of it left. My uncle went from Haralambos Kontozisis to Bob Wilson. My sister desperately wanted a nose job. We hadn’t seen our grandmother in years. It was easier to assimilate than to fight like Greeks. Of course, Greeks had fought assimilation before, but they had the luxury of being in the country at all times, surrounded by folks who understood completely. Greek America was waning.

I had to salvage something. I was filled with longing, and for once it could not be soothed with spanakopita (although, gemista almost did the trick). That must have been why Greek music was so monumental to me. The fact that my heritage had survived almost solely through me was monumental, and I did it through music. I had always known what I was, but perhaps not who I was, or why it should matter at all. To sing in Greek meant something had finally reached me. I had touched something that had long been elusive or misunderstood. Whereas everyone else saw Greece as a bleached fantasyland or vacation spot, I saw it for what it was. Small, wronged, often jagged, inexplicably beautiful.

To sing in Greek meant I was winning the fight, I suppose, against time and all of the shame I observed. Music could never be taken away from me. Once I learned a song in Greek, it could not be stolen from my memory. Against all odds, Greece had survived in me. I had caught it in one hand as it blew in the wind above my head.

Around the same time, I was burning CDs for people. It was a hobby I had picked up one August when I needed a sentimental birthday gift for a friend, and I fell in love with physical forms of music. I also made cassette tapes, but who in my life really owned a tape deck other than me?

I made two CDs for my mother, both about 23 tracks of my favorite Greek songs. It was the easiest way I could say a million things at once: are you proud of me? and remember this? and I wish you had done this for me. In a way, I always felt like I had to prove myself as Greek, even to my own mother. I wanted her to see me, and see how hard I really was trying. I wanted her to see beauty in herself, not shame, and hear how I loved Greek music. I wanted something to share, too, seeing as I hardly knew any other Greeks. Only she knows if all of that got across, but her pride was everything to me. She played those discs ad nauseam.

That, for me, was the internal validation. Then there was the music at festivals—the external validation.

All Danbury residents are more or less aware of the Greek Festival that Assumption puts on every June. It’s one of my favorite parts of the summer, but the whole reason I go is for the dancers and the music. There’s almost no greater joy than clapping along to Τσιφτετέλι—the collectivity makes you feel part of something instinctual. And the fact that going to Greek festivals is such a long-standing tradition, both in Greek culture and in my family, makes it all the more moving. We all have a special connection to the music and dance that we’ve forged over time. Sometimes I watch my mother close her eyes against the music and it’s like watching her get in touch with something intangible; something only she knows.

Πανηγύρια (festivals) are such a distinct and intrinsic part of Greek culture; they’re one of the things we brought with us to our American enclaves despite only having room for the necessities. Where some would say the festivals are a waste of time, loud, unintelligent, or full of liquor, we say they’re crucial for survival. How could we go on in America without song and dance? Without togetherness? We could not.

Greek music, most importantly, is built on covers. I’m sure this is something present in all cultures, but I’d always admired how a Greek folk song got recorded and restyled a million times by different people, and everyone knew the song like a heartbeat. Any Greek folk song you hear is guaranteed to have been covered and recorded a dozen times already. One of my favorite examples is Το Μαντήλι (The Handkerchief), which, if you look it up on Spotify, immediately gives you upwards of 20 unique recordings. They’re all uniquely sung, too, and some have been modernized with electronic elements. Το Μαντήλι is a song that practically every Greek, native or diasporic, knows by heart.

It’s very symbolic, in a way—no matter how the song gets changed, the lyrics and melody are the same, and they never lose meaning or specialty. Whenever I sing a song from an ocean away, I do the same. The library of Greek music stands on the traditions of oral storytelling, rituals, and folk songs that got passed around villages. Songs we sang in chains, on boats, in our backyard gardens, on the trails to asylum out of Asia Minor.

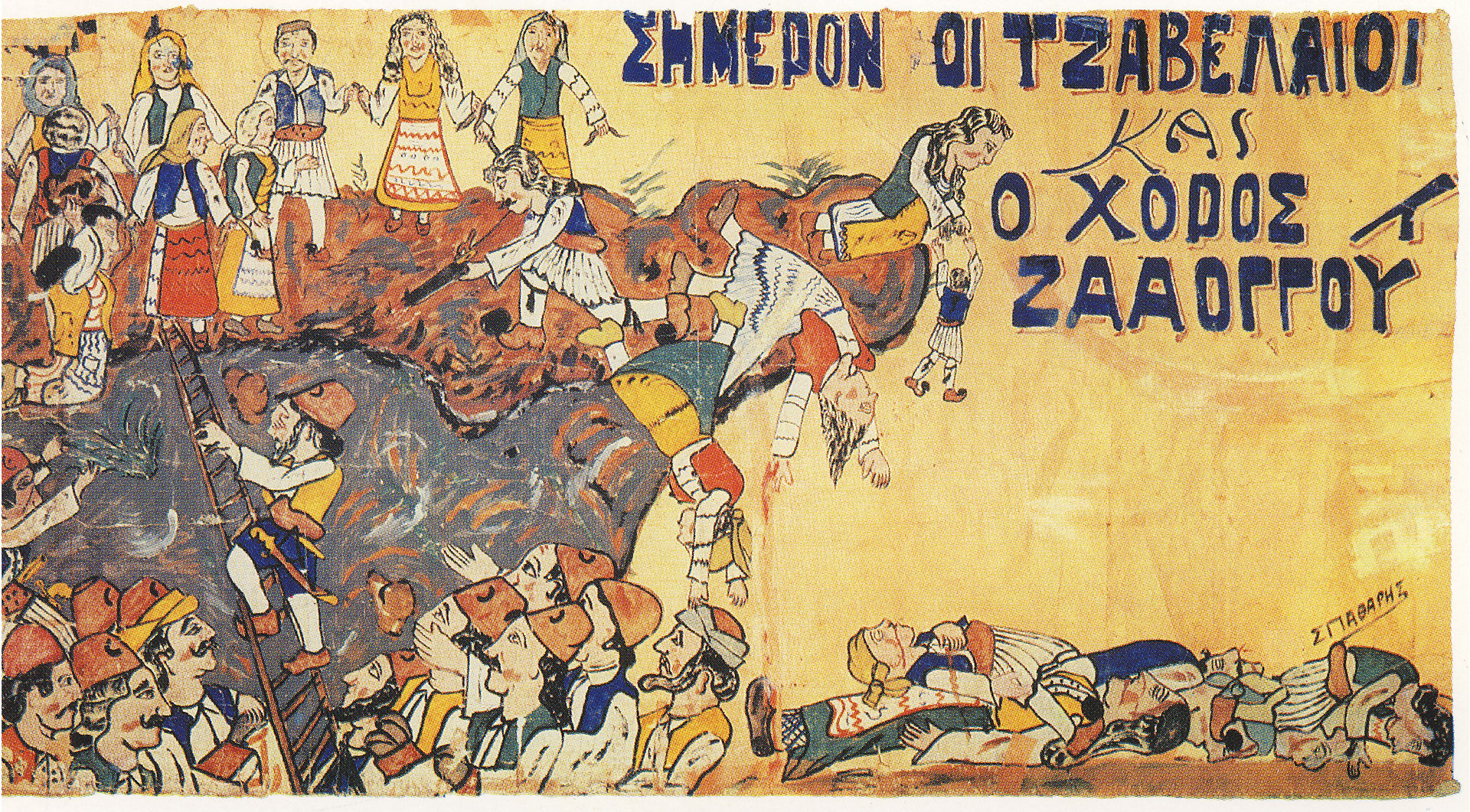

In fact, on December 16th, 1803, a group of Greek women danced and sang to their deaths as a means of escape from Ottoman invasion. Many of them pregnant or holding their young kids, the women danced in a line and sang together as each one jumped off a cliff before the Ottoman soldiers could find and kill them. It was a means of self-sacrifice, as well as maintaining their dignity, but most importantly a means of staying united in dance until the very bitter end. They were from the region of Epirus, too—where my own great-grandfather was born and raised, and where my great aunt says no one ever made it out of. The event is now referred to as the Dance of Zalongo, or Ο Χορός του Ζαλόγγου.

Today, their dance is still performed, in honor of the Souli women. In the book Imaging Souli: Interactions between Philhellenic Ideas and Greek Identity Discourse, author Ewa Róza Janion says that “dance expresses the unity of love and death, one of the deepest existential paradoxes.” For Greeks, dance binds us—to each other, to life, to death, to music.

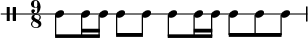

Traditional Greek music has many specific dances like Ζεϊμπέκικο (Zeibekiko), which can be danced to many different songs that share one common rhythm and time signature (in this case, 9/8 or 9/4).

![]()

These dances are each sort of a subgenre of λαϊκά (traditional folk songs) and most Greeks can identify dances by rhythm. Many of us also know how to dance them, which is just another avenue of connection through Greek music that happens every day. It’s hard not to be connected—when Greeks dance, we do it in a circle, facing our community members and locking arms with them. It’s both a physical and figurative knot of people. Knowing the music made me feel at home, but then, if you didn’t know the music, were you really Greek at all? How lost would I feel today if I hadn’t reconnected?

Today, I’ve gotten so comfortable in myself that Greekness is no longer a spectacle. Unfortunately, there are a lot of second-generation immigrants like myself who don’t feel culturally seen or like they have an identity unless it is on display, being acknowledged, being named. Of course, it’s a source of pride and joy for me, but it’s not something I need to be drenched in all the time. My heritage appears naturally, and it finally exists when nobody is looking. Still, that was something I fought for.

Being Greek is easy; it’s just a matter of being born. Remaining Greek when you live in a diaspora… that requires effort. Of course, maybe the effort isn’t visible, because oftentimes Greek-Americans grow up so submerged in their own culture that they don’t think about it at all. But let just one generation grow up isolated from family, and suddenly they’re fully American. As generations go on, it becomes increasingly more difficult and more important to know and appreciate your own heritage.

Greek music was family where none existed anymore. It was accessible, relatively familiar, and captured so much of Greece’s beauty. For those struggling with their cultural identity, starting can be as simple as a song. If you’re Greek, it can be as simple as… ωπα!

This has been the third installment of the new musical column Sound Check with Jules. Tune in next week to hear about music history, review, recommendations, analysis, culture, and more! For the Greek playlist I listened to while writing, click here.