Country music gets a lot of flack. Too much, if I do say so myself. I can’t count how many times I’ve heard, “I listen to everything—except country.” People say it like it’s a plague; the symptoms, of course, being harmonicas and fringe and Dolly Parton-esque acrylic nails.

What’s interesting is that most people who are like this grow to love country when they learn about the roots of it. Country music today is polished. It’s produced to play in stadiums, on chrome guitars. It can get so over-produced that it feels disingenuous, and far from the humble origins of country music. Country music was always more related to blues, gospel, and folk than pop or rock. It began as a distinctly Black, working-class genre, for folks who sang to the rhythm of work.

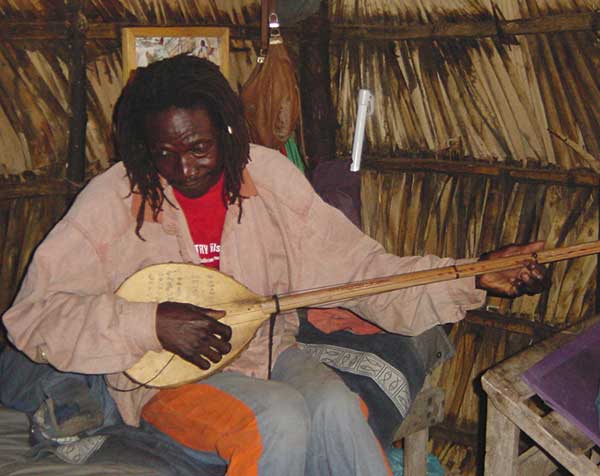

In fact, white people didn’t sincerely pick up banjos until the early 20th century. The banjo is a direct descendant of West African lutes like the akonting, an instrument made of a gourd with strings attached to it. It traveled to the Americas during the Atlantic Slave Trade, and made its home in the hands of enslaved Africans.

I’ve been workin’ like a man — Valerie June

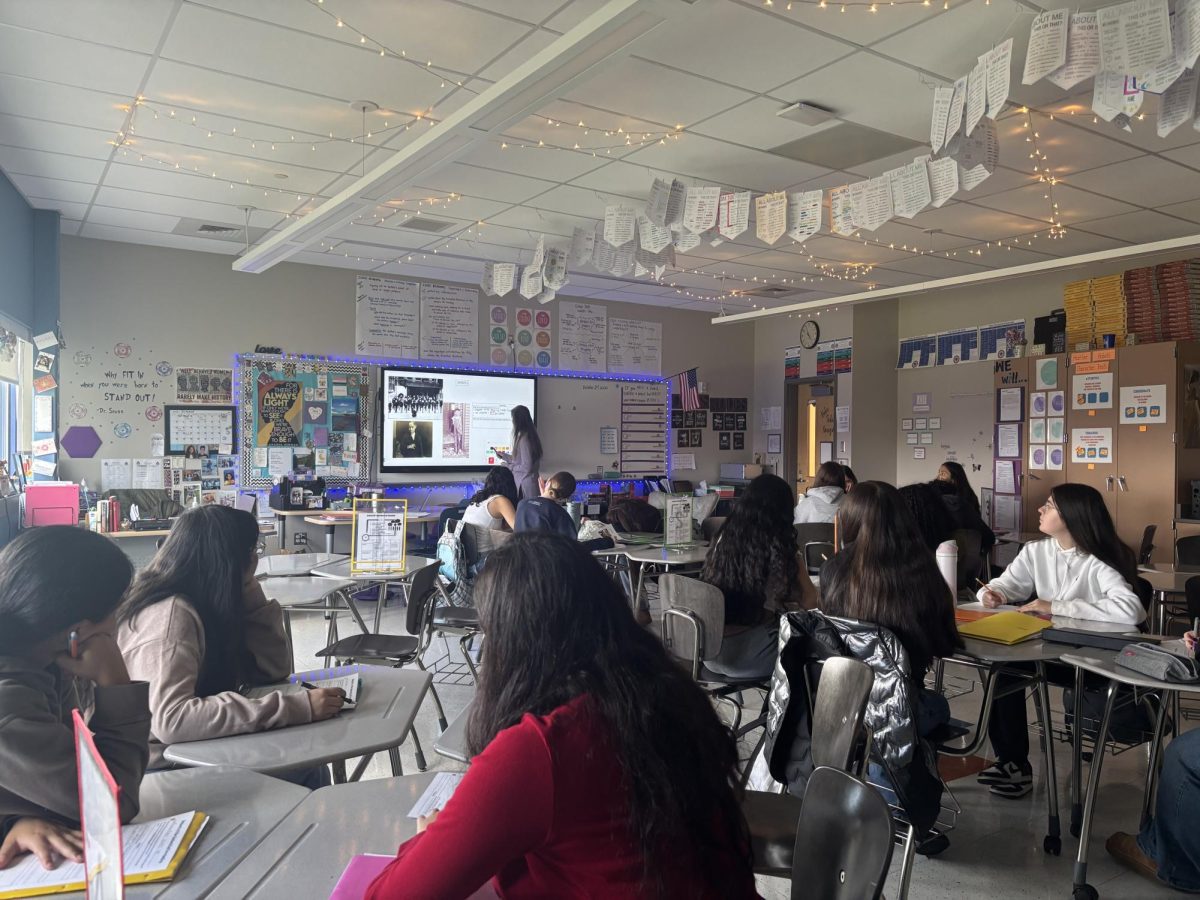

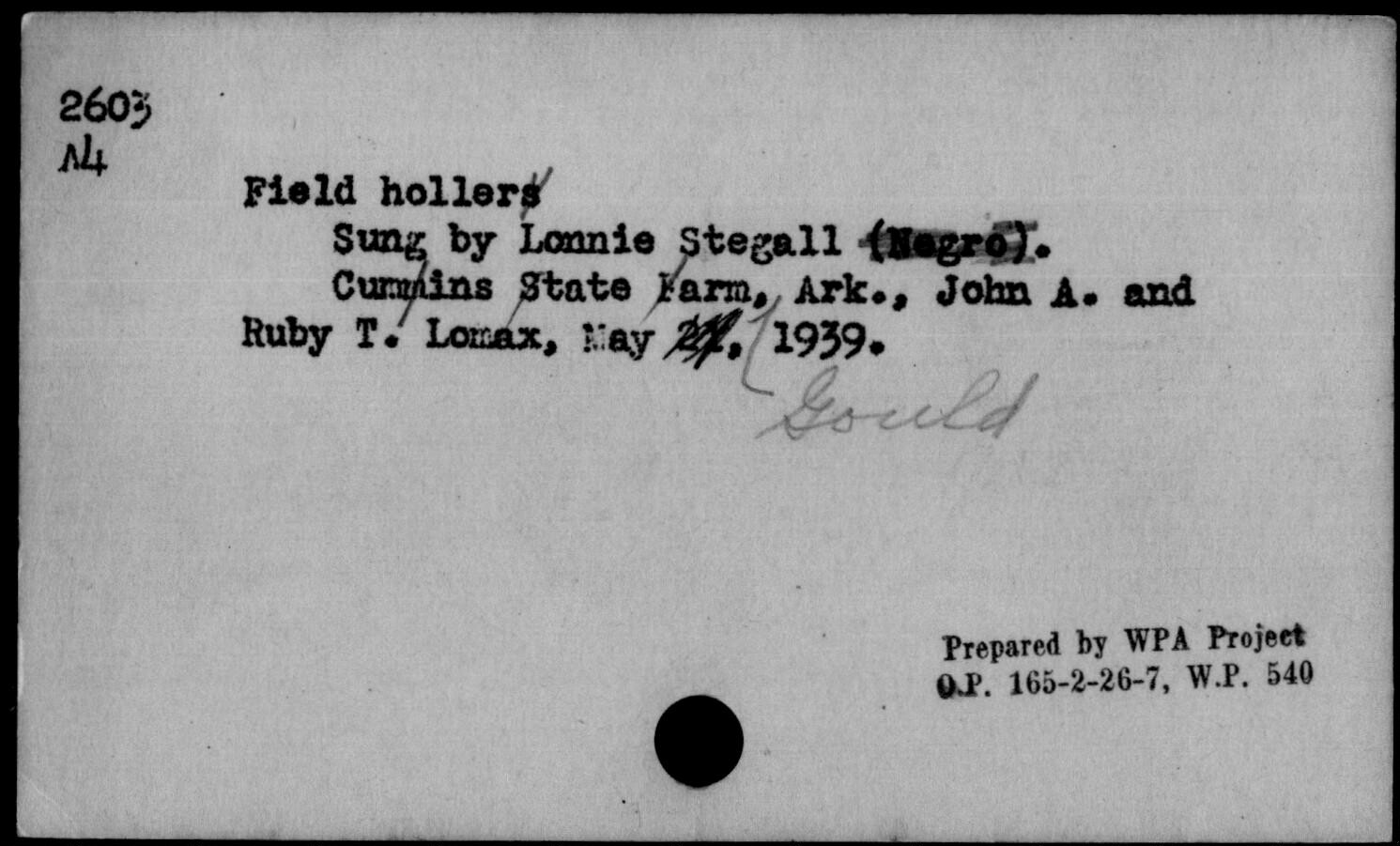

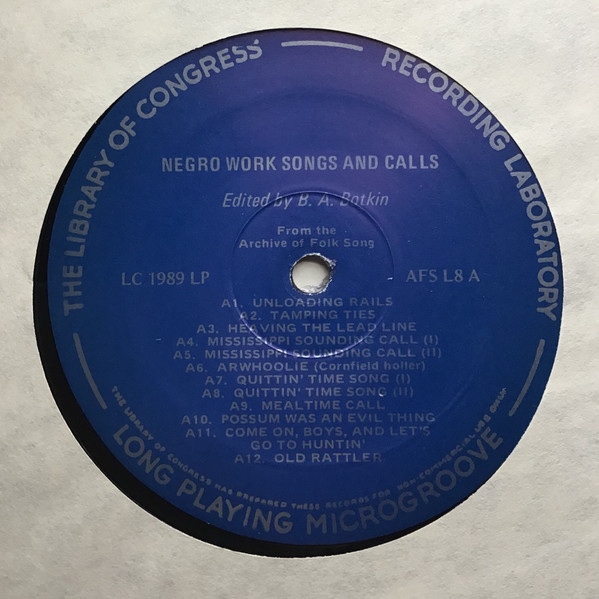

Trying to bring some sense of home and comfort into the brutal scene of plantations, they sang while they worked, for a number of reasons. Some work songs mocked the oppressor, while others communicated across fields (these were called field hollers). Work songs were also a crucial avenue for expression; enslaved folks vented their frustrations, built connections with others, dreamt of escaping the plantations, and even prayed (this would soon become the gospel music famous in Black churches).

A common feature of these work songs that would later make it to genres like country, gospel, blues, and jazz is call-and-response. It’s a staple feature of traditional African music where one person calls, and the other… responds. Not only was it a way to make a connection with the other person, but it was a reminder of home—of freer and simpler times. My all-time favorite example of call-and-response is this live performance by Nina Simone in New York, 1968. Commenters notice how the call-and-response element completes the song and makes it feel much more communal. The barrier between Simone and the crowd has been broken; they’ve been invited into the music. To me, it’s reminiscent of ad-libs in rap, another genre pioneered by Black-Americans. Oftentimes concertgoers will shout along to the ad-libs rather than the actual lyrics, creating that call-and-response dynamic. But I digress. Let’s return to African traditional music.

It’s a long way home — Clarence “Gatemouth” Brown

Here, we can find not just the roots of country music, but blues and jazz as well. Specifically, the Congolese Luba tribe’s music is one of the oldest examples of blues-like music. Their instrumentations are based around the dominant 7 chord and sung with a flat 3rd—that’s music speak for creating tension in the sound, just like the blues. The Yombe tribe, west of modern Congo, also sings in a flat 3rd over a major key. You can check out examples of this music here and here. Try to hear the bluesy roots!

These musical theories translated across the ocean, too. Blues and jazz thus began as distinctly Black, working-class genres. Blues was sort of the successor of plantation work songs, as it expressed very similar themes to work songs in a post-Emancipation Proclamation world. Blues exploded in Black spaces, especially “juke joints,” where Black-Americans would go to dance, sing, drink, and gamble after work. Jazz would be born last, in the 20th century.

Today, blues and jazz are still relatively Black genres. When we think of jazz, we think of Louis Armstrong, Billie Holiday, Ella Fitzgerald… all Black stars. Blues conjures images of Blind Willie Johnson, Fats Domino, Bo Diddley, and more. But country…? Most of us are thinking of pasty-white men in cowboy hats, sitting on hay bales. These men didn’t take country music seriously until it could be capitalized on.

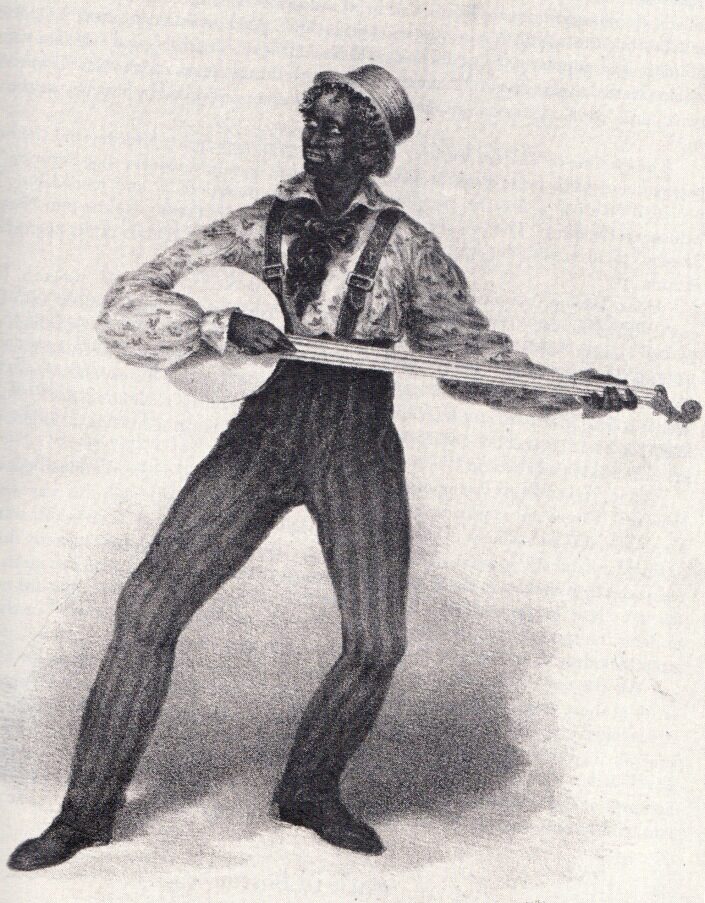

I wouldn’t treat a dog the way you treated me — Bobby Bland

I briefly mentioned banjos earlier in this piece—I omitted how these instruments had a strong presence in racist minstrel shows of the 19th century. White performers used banjos to mock and dehumanize Black people, and then took over the instrument. Joel Walker Sweeney, one of the most popular banjoists of minstrel shows, even has a plaque calling him the popularizer of the banjo. But the banjo had been popular for decades—it just wasn’t considered mainstream or worth attention until white performers could make money from it.

The banjo underwent many structural changes to appeal to white audiences and create distance between the instrument and its African roots. Frets appeared on the necks of banjos, as did pearls and decorations. White people created troupes and records around the banjo, which was now a “sophisticated” instrument. Black banjoists began picking up the guitar in the 20th century, as a way of innovating in jazz composition.

Today, the banjo remains a symbol of white country music. Beloved country songs, such as Lovesick Blues, are hailed as the first modern country songs and yet take inspiration from Black banjo country (or its stereotyped portrayal in minstrel shows). White minstrel performers literally sang and played instruments the way they thought Black people did, and rebranded that as country music once they took the blackface off.

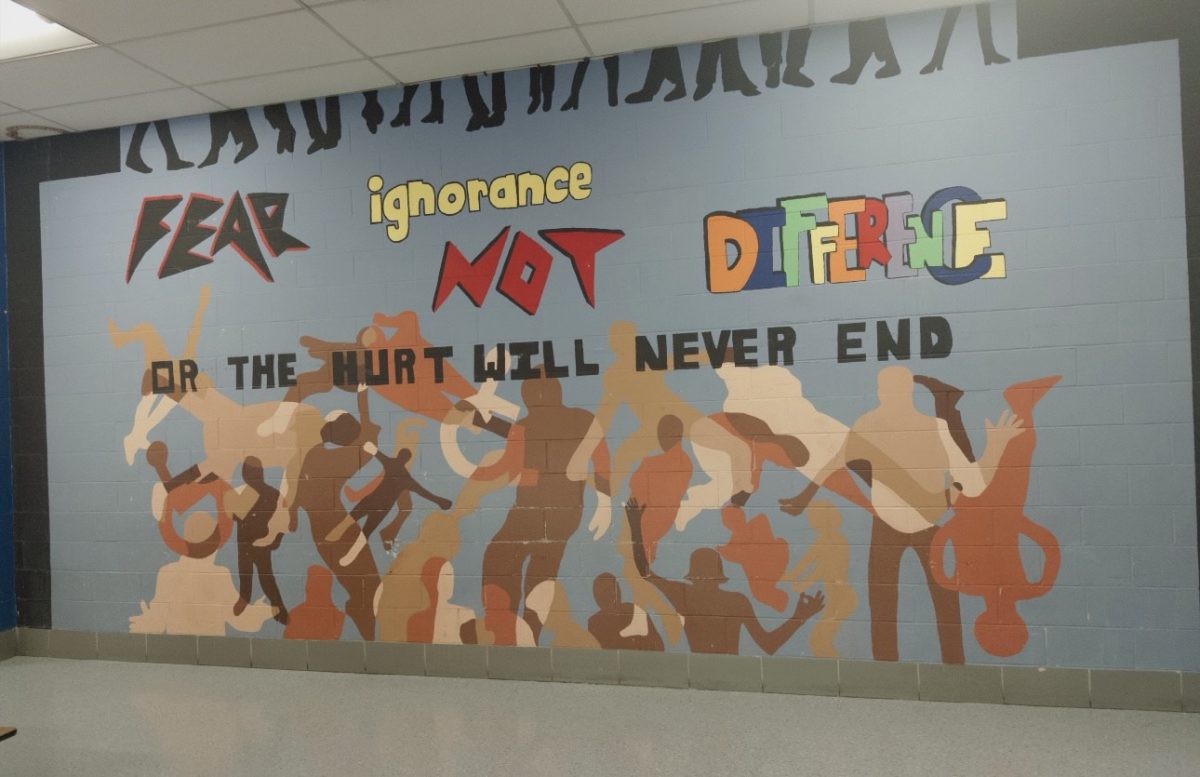

This pattern became frequent over American history—Black musical characteristics were adapted to be palatable for a white audience and then exploded in popularity. However, white people were the only ones ever credited or taken seriously in these genres.

Something is holdin’ me back / Is it because I’m Black? — Syl Johnson

This brings us to the modern state of country music. The country genre was one that Black-Americans built up with various African and American influences, as well as their own personal experiences. White people of course influenced the genre, too, adding on and changing some—especially working-class white musicians who learned to play country from Black people. They played to the same laborious rhythm that Black folks did while working on plantations. But if country was originally a Black genre, or at least built from Black music, why do we only see white people? Just this month, Tracy Chapman won Song of the Year at the Country Music Awards for her single “Fast Car,” being the first ever Black person to win the award. And the reason why she won the award in 2023 for a song from 1988? A white artist, Luke Combs, covered it. Not a single Black person has won the Country Music Association Award for Album of the Year, which began in 1967.

The music industry is historically exclusive, especially favoring the rich and the white. As such, country music has gained the appearance (at least to outsiders) of being close-minded, white, and inaccessible. It’s exactly everything that country roots are not.

That’s why it was such a big deal when rapper Lil Nas X, a gay Black man, won 2 Grammys for “Old Town Road,” the country single that spent a record 19 weeks at number 1 on the Billboard Hot 100 chart. The song had an almost ridiculous tone, and was a bit unexpected, but the public (and the radio) welcomed it with open arms. The track soared beyond country and rap scenes. It was refreshing to see Lil Nas X take hold of a genre that had so blatantly excluded Black people—not to mention the way he has been excluded from rap spaces for his sexuality, but I digress.

“Old Town Road” was actually removed from country charts for “not being country enough.” But hip-hop and country can coexist. Historically, they do. Hip-hop is known for taking samples and inspiration from other genres and blending them into something new. Just look at chopped-n-screwed hip-hop, a subgenre whose entire premise is remixing and “chopping up” other songs.

Of course, we have to wonder if the track’s removal is actually because it’s “not country enough” or because Black people are not the modern face of country music. To maintain such a white history of chart-toppers and award-winners, the music industry has to systematically exclude certain folks. Is this not a case of that? Or is “Old Town Road,” which talks about horses and tractors in a Southern accent, features Billy Ray Cyrus, uses a country rhythm and instrumentation, really “not country enough”?

I go anywhere that I wanna go / ‘Cause I’m Black myself — Our Native Daughters

The reclamation of the country sound and aesthetic into Black spaces goes beyond Lil Nas X. One of my current favorite country musicians is Valerie June, a Black Tennessean who blends country, soul, folk, and R&B. My favorite track of hers is “Tennessee Time,” a country ballad with charming strings and a waltzing rhythm. As a Black woman, June feels as though she is expected to make her music political. She cannot simply exist as a Black woman in the country genre, making the music that is hers—there has to be a commentary or acknowledgement of her race.

June is “f—king joyful” that she’s been able to open doors for Black women in country music. At the same time, she says, “I don’t want to spend much time explaining why it’s okay for me to do it. I just want to spend my time doing it.” She doesn’t have to make her race known or turn herself into a political statement with every release. By making music without apology, she asserts that Black country is going to exist and be great regardless of if it tops charts, makes a commentary, or is even accepted as country. After all, why should she apologize for something she is entitled to?

It’s depressing to look at the country scene and think, there’s something that will always be exclusive; especially because there always have been and will always be Black country artists. Especially because most of us agree that the Grammys are rigged, and whether an artist makes sales is up to the listeners. If we want to see more Black people succeeding in the country scene, or we don’t like how the face of country is misrepresentative, we as the listeners have a hand in changing that. We have the decision to stream, to buy records, to show up at concerts.

Country music gets a lot of flack. It’s not just an echo-chamber of white men and their ivory guitars, though—and if it was given a chance, we would see its expanse and charm.

This has been the 4th installment of the musical column Sound Check with Jules. Tune in next week to hear about music history, review, recommendations, analysis, culture, and more! For the Black country playlist I listened to while writing this piece, click here.