Recently I had the pleasure of seeing a MET screening of Florencia en el Amazonas, an opera by Mexican composer Daniel Catán about the fictional opera diva Florencia Grimaldi, her trip along the Amazon River, and the passengers that accompany her. Florencia draws inspiration from magical realist ideas like in the writings of Gabriel García Márquez or Pablo Neruda (whom you may be familiar with if you took English II).

Each character in Florencia has their own distinct arc and reasons for being on the odyssey through the Amazon River. The ship is supposed to be going to one of Florencia’s concerts, which is the surface-level reason for everyone’s boarding, however, something deeper is afoot for each of them. Florencia is searching for her long lost lover, Cristobal; writer Rosalba is searching for the elusive Florencia to finally interview her and complete her biography; lovers Alvaro and Paula are looking to reignite their flame; and Arcadio, the captain’s nephew, is trying to escape his destiny of becoming the next captain of the ship. The story is told in two acts, and each character undergoes growth and change, learning something new about themselves and even falling in love. Florencia is a beautiful, innovative exploration of how love transforms, and yet, how it survives.

Magical Inspirations

It is a very distinctly South American show, with references to geography and colorful dancing puppets of exotic animals. Magical realism is a pillar of South American literature and storytelling—it took hold during the twentieth century and allowed writers to connect with spiritual influences as well as comment on real-world topics through metaphor. The essence of it is that magical elements can exist in a realistic setting and the characters will respond to them as normal. In a way, magical realism also plays with the idea that magic is everywhere, and the physical world has a connection to the spiritual world.

The most potently magical-realist part of the show is the climax, during the storm, when the Captain is knocked unconscious. The mystical shipmate, Riolobo, communicates with the spirits of the river to briefly bring the ship into a purgatory state between magical and real, living and dead. Riolobo seems to break the fourth-wall throughout the entire show, acting as a medium not just between spirits and humans, but also between the audience and the characters onstage. During the storm, he pleads with the spirits, telling them not to destroy their world, and lamenting how the river takes hold of the entire land. The river is an ambiguous symbol throughout the show; it could represent love, or it could represent fate, or it could be a more literal commentary about how the geography of our homelands changes us as people. Perhaps because of this thrashing river, the people of the Amazon feel ungrounded in everything, and are at war with themselves. They are at the mercy of the land and the weather. Again, these elements make Florencia distinctly South American, and elevate the show overall.

Musical Reflections

Musically, Florencia incredibly showcases a range of emotions and tones. For example, as Paula and Alvaro argue over whether they should eat the iguana special at dinner, Paula uses short, high notes, accompanied by punchy marimba, while Alvaro uses deep, long notes, creating a contrast between them and bringing attention to their differences. The composer also makes use of layering the performers’ voices, at times creating chaos and at others creating union.

Toward the middle of the first act, the two couples—Paula and Alvaro, and Rosalba and Arcadio—are playing poker on the ship when Paula and Alvaro break out into another fight. Their voices continue to contrast, playing with off-kilter half-steps to mimic an annoyed, combative tone. They sing with dissonance, “Esa es la diferencia,” fighting for musical dominance. Paula points out how well Arcadio plays compared to Alvaro, while Alvaro stubbornly points out Rosalba’s beauty and talent. Their notes are only resolved into a harmony when Arcadio and Rosalba join in, suggesting that Paula and Alvaro cannot work together on their own, and that Arcadio and Rosalba are, by contrast, such a melodious pair.

Later, in the second act, the ship is taken by a brutal storm and the passengers are separated. Arcadio and Rosalba reunite in their duet, harmonizing instantly, even as they woefully sing, “Ay de las almas que sufren por amor.” In this song, although the two are rapidly falling in love with each other, they insist that they have seen love tear couples apart and drive them to hate, and they cannot bear witness to that again. As they bid goodbye to unhappiness, they also bid goodbye to a budding love. This is one of the moments in Florencia where the lyrics really get to shine, with lines like “He tocado la piel de quienes que ya no se aman pero duermen juntos”—“I have touched the skin of those that no longer love each other, but still sleep together.” The strings swell into a romantic but sorrowful sound, withering as Arcadio and Rosalba exit the stage.

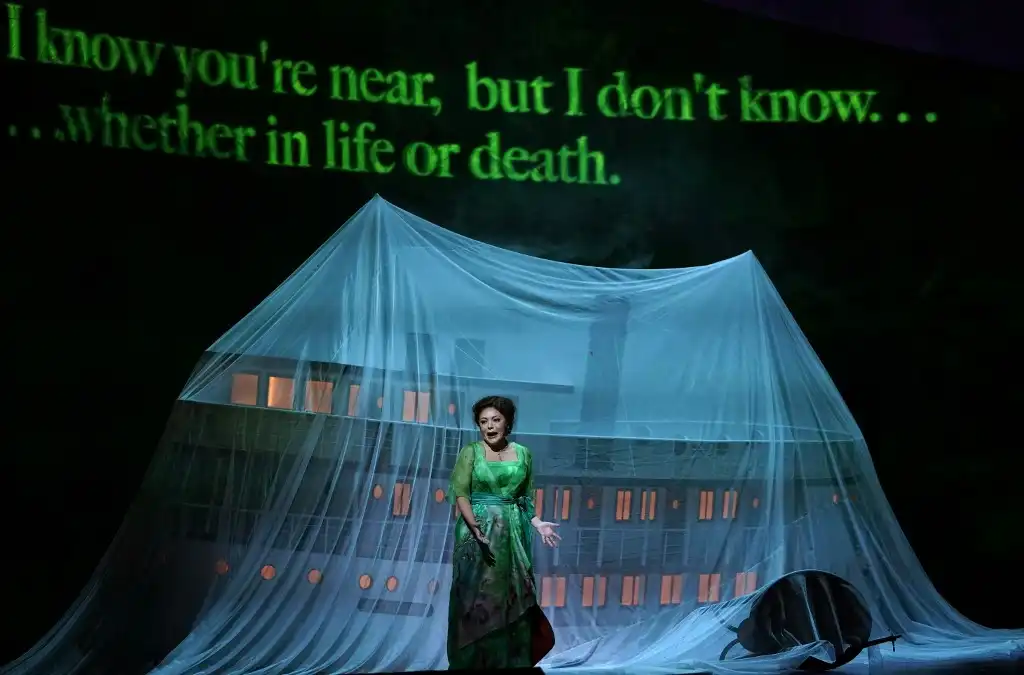

This line summons the image of Alvaro and Paula, who are now both emotionally separate and physically torn apart by the storm. Their love has taken them to tragic places, and, as we will see in the following song, continues to be the source of their pain. They cannot leave each other because they still cling to the love they used to share. Paula, believing Alvaro died in the storm, croons, “¿Alvaro, cariño, que haria sin ti?” She mourns him because she believes so deeply that rekindling is possible, reinforcing the opera’s central theme of everlasting, albeit changing, love. In this song, Paula finally realizes that it is not a lack of love between them, but too much pride—“Se llama orgullo. Ninguna muralla es tan alta.” Ironically, what the pair needed was not more time together, but time apart. Love’s hand cannot be forced, and must instead be followed. The orchestra now beautifully complements her voice, rather than combating it, giving the listener a sense of closure.

Visual Reflections

Being set in the early 1900s, Florencia had all kinds of beautiful night-dresses and suits to offer. Every piece of clothing not only complemented the performers beautifully, but also the time period; I was immediately able to recognize the era of the show. Whether decked out dazzling sequins and jewels, or sweeping swaths of fabric, or simply in a classy off-white suit, each costume settled perfectly into the show.

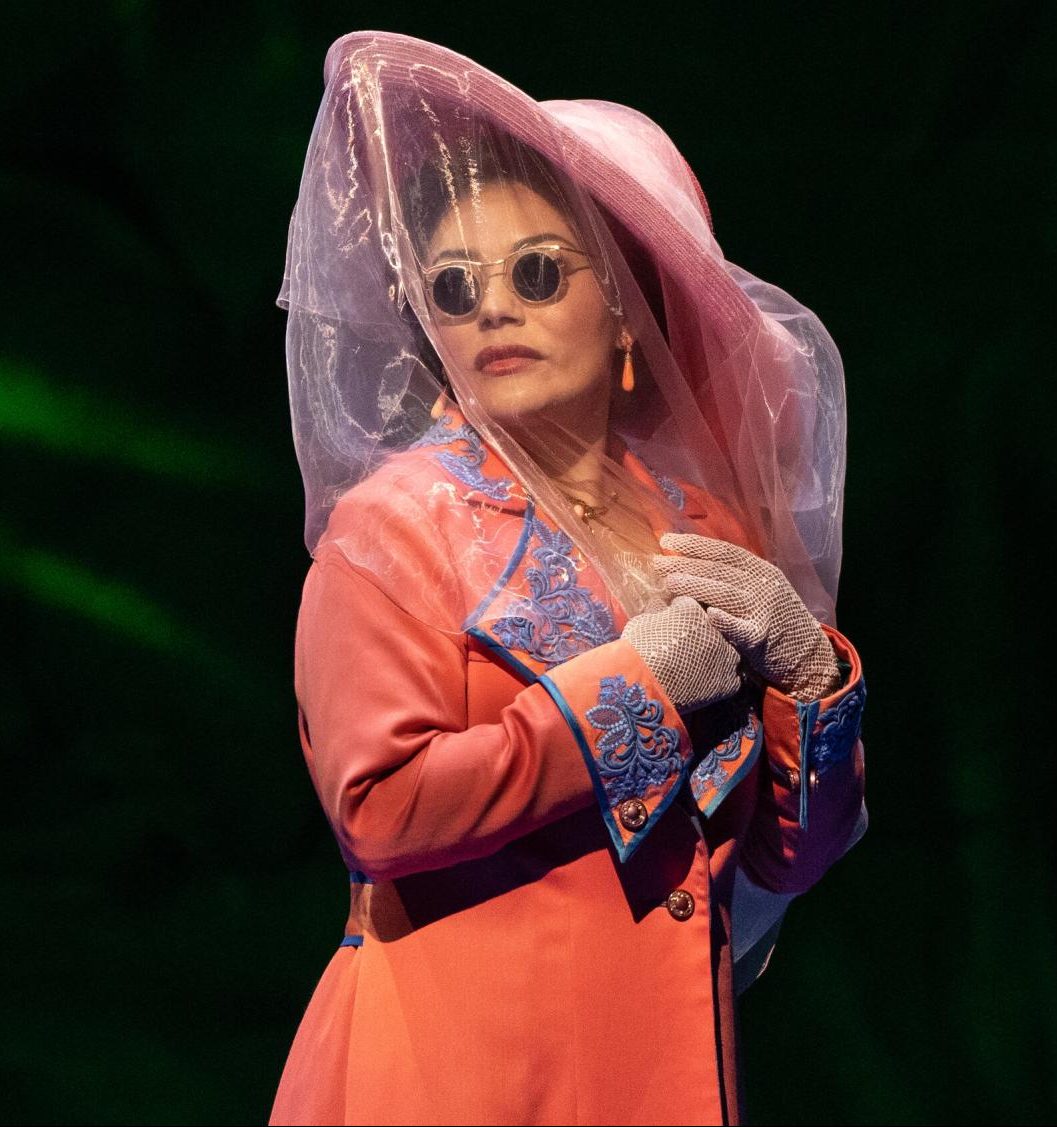

At the beginning, Florencia Grimaldi is given a veil over her face and sunglasses over her eyes, driving home the fact that she’s a mysterious figure that everyone loves, but no one knows. She’s beautiful, or at least the idea of her is. Florencia seems to represent something different for each character, and the veil is a perfect symbol of that. It is only when Florencia can begin to tell her own story that the veil and glasses are physically lifted.

Perhaps the best visual part of the show was the dancers. Once again playing with South American culture and expression, Florencia is adorned with vibrant dancers and puppets, all mimicking the animals of the Amazon. It makes the show feel truly magical, with intricate costumes of birds of prey and iridescent fish heads. There are even women dressed as deep pink lotus flowers, drifting along the edges of the ship as Florencia sings. The animals of the Amazon, along with the geography itself, are like a spiritual force bigger than all of the characters, as they constantly loom over the show and influence it in subtle ways. From the storm, to Alvaro and Paula’s iguana argument, to Riolobo’s communication with the animals, nature is a power greater than all of them, no matter class or creed. In a similar vein, nature is deeply intertwined with how humans feel, portray, and perceive emotions like love. This is expanded upon at the very end of the show, during Florencia’s transformation.

Where It Leaves Us

After searching for Cristobal and finding naught, Florencia sings a final solo song which she finishes by becoming a butterfly. Whether you interpret it as a homecoming, an acceptance of Cristobal’s disappearance, or a realization of her full potential, Florencia is being changed by love. As she turns her back to the crowd and allows her wings to open, the opera comes to completion, and the themes of love are perfected.

The finale is a perfect summary of the show; Florencia has gone on a journey for love, with one intention, and has come out of the other side with a different but true purpose. She has reached a state of spiritual advancement, connecting with the magical animal world—but also with her humanity. Becoming a butterfly, while being in love with a butterfly hunter, is Florencia opening her arms to how her love has grown and changed with her.

Florencia en el Amazonas is an innovative, beautiful exploration of familiar themes. It is an homage to humans, to our geography, and how the two dance and clash. Coming out of the show, I felt that opera was no longer a form of art that was too inaccessible to get into. I no longer felt that opera was too highbrow, nor hard to connect with—rather, Florencia had brought me and every other audience member to a plane of honesty and pure human emotion that was simply too beautiful to ignore.

This has been the eighth installment of the musical column Sound Check with Jules! Sound Check will now be on a biweekly schedule. To watch a production of Florencia en el Amazonas for free, click here!