Raucous men, provocative dance sequences, and a woman in a low-cut outfit. This is a recipe for the classic Bollywood item song. Many Bollywood movies are essentially musicals, often with an item song with little to no plot relevance. Songs like “Dilbar” in the movie Satyameva Jayate or “Chikni Chameli” in Agneepath are chucked into movies as a cheap method for gaining popularity. This popularity comes from not only the catchy, upbeat music of item songs but also the blatant objectification of women.

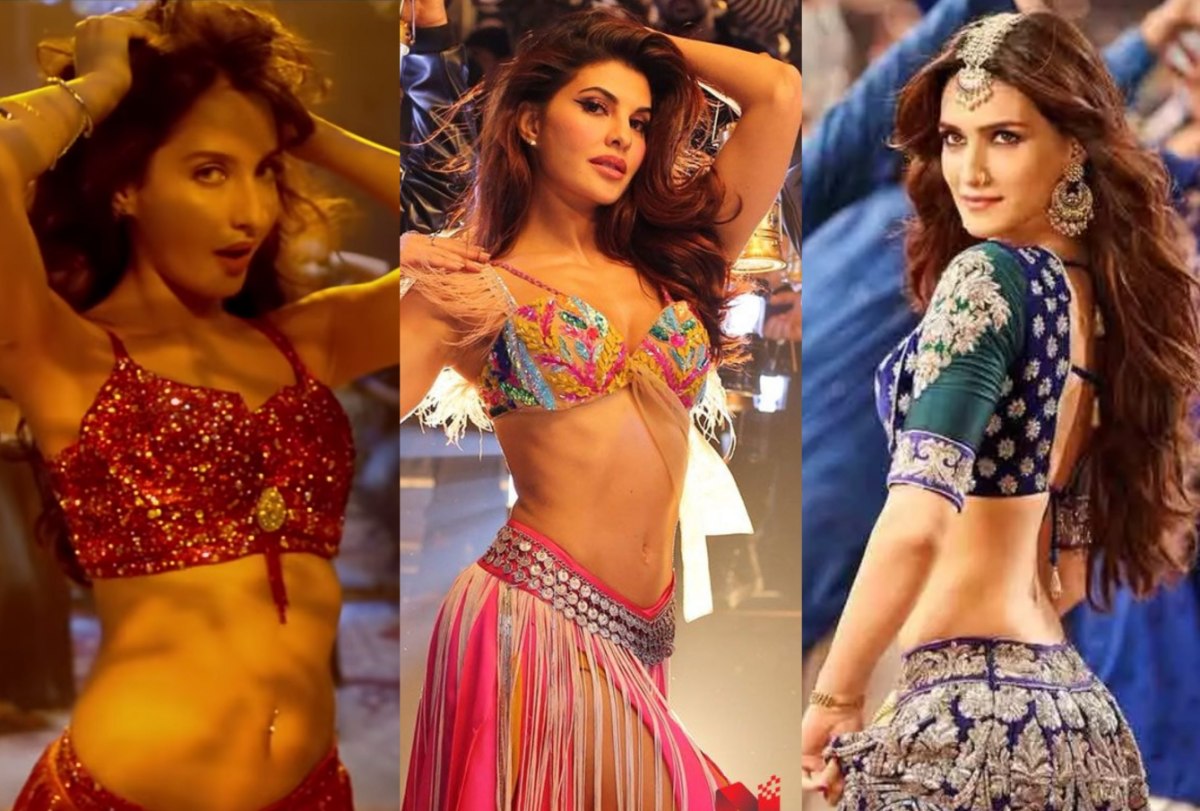

via Times of India

Take “Chikni Chameli,” for instance. The nameless female character, played by Katrina Kaif, finds herself as the only woman in a room filled with drunk, belligerent, gun-touting men. She dances as hundreds of such men watch on, with certain shots zooming in on every last bit of exposed skin. She sings of her halwa, an Indian dessert, and how she will “serve it lovingly.” Along similar lines is the song “Munni Badnaam Hui,” whose title translates to “Munni was defamed.”

The main purpose of these songs is to simply present women as “items” to be ogled and overly sexualized. Rather than being real characters, these women go unnamed, only showing up for the two-minute bout of degradation. A study by Amity University Mumbai noted that in these scenes, “women are presented as passive and powerless and serve as objects of male desire. Going far beyond highlighting a woman’s to-be-looked-at-ness, cinema builds the way she is to be looked at into the spectacle itself.” The male gaze, the study added, is embedded into these songs. Often, these women drape themselves across the hypermasculine male protagonists, playing further into the power dynamics of these sexist structures. The focus on bare skin, the draw towards the woman’s sexual allure, the men’s possessive hands grabbing at the woman all show the male gaze used to produce these scenes.

However, it is important to consider the actresses who use item songs to empower themselves and take agency in their own sexuality. After all, dancer Nora Fatehi has made a career out of her cameos in item songs, from “Dilbar” to “O Saki Saki” to “Kamariya.” Nevertheless, this very genre encourages its audience to sexualize women, treating them as objects to be stared at. It normalizes this needless objectification and pushes forward harmful sexist beliefs about the value of women. A University of Allahabad study found that “male college undergraduates who viewed highly sexual hip-hop music videos expressed greater objectification of women, sexual permissiveness, and stereotypical gender attitudes than {those who do not}.”

Whether these item songs are reflections of society or are intended to influence it, they present a worrying future for the representation of women in Bollywood and other media. Clips of these songs rack up nearly 500 million views on YouTube, calling attention to just how broad their audience is. As the newest releases in the Mumbai box offices inevitably add to the hundreds of songs within the genre, we must wonder when the industry will take action. How much longer will we have to see raucous men, provocative dance sequences, and women in low-cut outfits? When will this objectification come to an end?