Heroin abuse on the rise, but DHS escapes trend

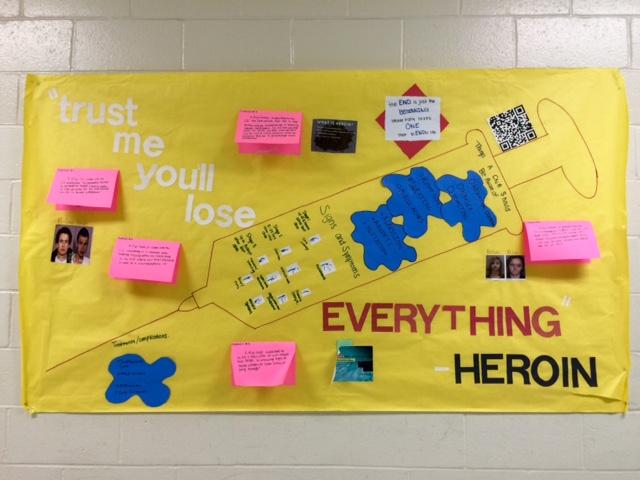

A bulletin board in B-wing raises awareness for fighting heroin use.

March 23, 2016

According to the Hartford Courant, there were 327 heroin-related deaths in Connecticut in 2014.

Since then, that number has more than doubled as 720 overdoses were recorded last year, 444 of them fatal.

Heroin abuse and overdoses have become overwhelming problems across the country, including Connecticut, with statistics higher than they have ever been before.

More than half of the 47,000 drug overdose deaths in 2014 were from opioids, including painkillers and heroin, according to a recent WSHU news report that quoted a CDC study.

Multiple high schools around Connecticut have also been struggling with the issue, as several town officials, along with Gov. Dannel Malloy, have been pushing for stronger laws to try to decrease the outbreak.

As for Danbury High School, administrators and counselors are grateful that the outbreak has been slow to make its way around the school.

Crisis Counselor Stan Watkins says that surrounding towns are having a larger problem with the drug due to their increased income.

“It’s been slow to hit here because other surrounding districts are more affluent,” he states. “Parents make more money so kids have easier access to the drugs/pills and heroin.”

Kathleen O’Dowd, coordinator of Danbury Public Schools Health and Nursing Service, seconds Watkins’ observations, saying that “although she has not witnessed any incidents, that’s not to say it won’t happen.”

Students as well have recognized that the heroin outbreak has yet to reach DHS.

Senior Kendra Beaver understands that surrounding districts are having more of a problem simply due to the fact that household incomes are higher and teens have access to the money needed to buy the opiod.

“I can see how other schools are affected by the abuse more than here at DHS,” she says. “Although there are still drug issues in our school, I have not heard anything about heroin abuse.”

Although there has not been a significant rise in heroin abuse here, Watkins has witnessed a rise in abuse of pills, such as Xanax.

“The rise in pill abuse makes way for the rise of heroin,” he explains. “The pills are easy to obtain and give people that quick but strong high that they are looking for.”

However, the pills soon become too expensive for many to afford.

Watkins says, “The pills are expensive and can cost $20-$30 for one pill. That’s when people move on to heroin because it is relatively cheaper.”

As fatalities increased across the state, the issue turned into a crisis.

In response, Malloy proposed legislation to further increase the use of an antidote to counteract heroin overdoses.

The drug, naloxone, is sold under the name Narcan and was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration on Nov. 2015.

Until recently, it had been issued to first responders. Now, a state law enacted in the fall allows for pharmacists to write prescriptions for its issue.

The FDA has deemed naloxone as a “life-saving medication that can stop or reverse the effects of an opioid overdose.”

When is comes to stocking naloxone in school nurse offices, the subject is still being discussed around the state of Connecticut.

Although it may seem as if naloxone is easy to get, O’Dowd warns that it is more than just getting a prescription.

“Legislation does not mandate that naloxone be stocked in schools,” she states. “With that said, it would involve policy development for stocking the medication, administration procedures, and staff training involved.”

With abuse and overdoses on a steady rise, there is a strong possibility that naloxone will soon be carried in schools around the state.

“I can foresee the possibility for naloxone being a drug the district would stock as we do Epinephrine for the treatment of life-threatening allergies,” O’Dowd says.

Although Watkins credits the antidote to saving lives, he still believes that there will be a problem with abuse.

“It will certainly decrease deaths but I don’t think it will decrease use,” Watkins says. “Those who have the antidote, though, need training on how to use it correctly.”