Among the surge of entertainment-based performances in the 19th century, there came to be one classless and ignorant act that unfortunately became the blueprint of today’s displays of microaggressions and racial stereotyping. Minstrelsy, the “formulaic comic routines based on stereotyped depictions of African Americans and typically performed by white actors with blackened faces” (as Oxford defines it), perpetuated racist ideologies and stigmas that has since left an irreversible mark. Minstrelsy was commonly seen in accordance with blackface, the act of white people altering their features by painting their skin black, outlining a large white mouth, wearing an afro wig, and colorful or worn down clothing.

In 2019, Margot Jefferson, a Pultizer prize winning critic, classified this insidious display as most often a “big white clown’s mouth, a hat, the over long tail coat,” and to put it simply “mocking”. It wasn’t just the appearance that white people tried to exaggerate; the behaviors of Black people were also ridiculed. These characters were always depicted as lazy, bafoonish, poor, etc. and actually lowered the self esteem of many Black citizens, as they believed this was how white people viewed them.

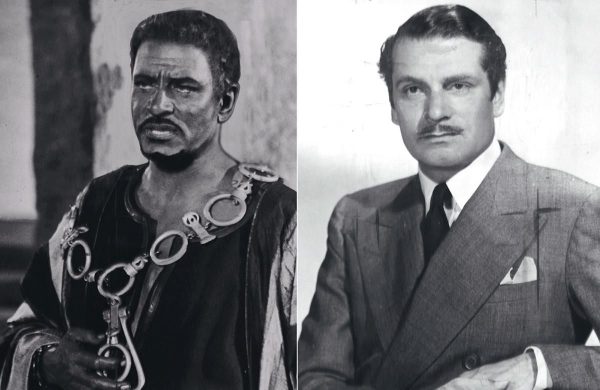

There is no exact timeline for when minstrel performances began, but there is a decent understanding of when the first few displays occured. In an 1824 execution of Shakespeare’s Othello, for example, the portrayal of low class working citizens in the story were prime cases of this mockery. The actor who played Othello for instance, was a white man who darkened his skin and altered his vocabulary and accent, saying things like “dat” instead of “that”, which can be deemed as a derision of African American Vernacular English as well.

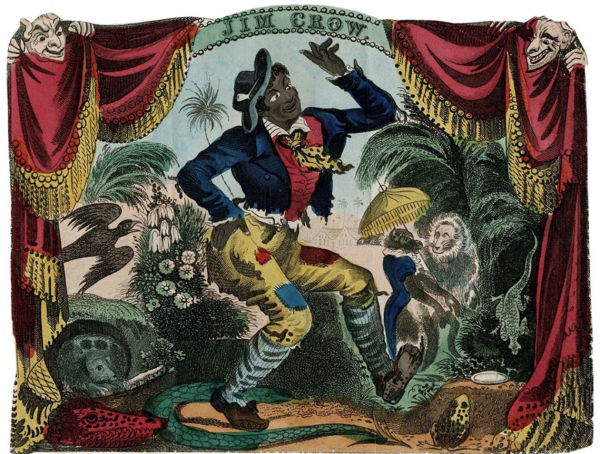

Following this act came the uprising of many others, eventually leading to the first official character depicting blackface in the 1830s by Thomas D. Rice, or his stage name, Jim Crow. Rice’s act consisted of darkening his skin with burnt cork, as his character would recreate dances he witnessed a disabled Black man doing in the story. Despite its problematic tendencies and the fact that it occurred at the expense of the Black community, this form of entertainment and the character of Jim Crow garnered a multitude of supporters, deeming minstrelsy as one of the most popular forms of entertainment at the time.

In spite of the blatant disrespect that was illustrated through minstrelsy, there continued to be an ongoing debate on the intentions and interpretations of those who executed it. Some researchers were adamant in claiming that blackface originated simply to uplift the white community and bring joy about those groups. They argued that there was no intention in putting down the Black community, and that Rice’s act was rooted in the appreciation of Black culture, as well as the guilt of slavery. Eric Lot, a professor at the City University of New York, personally describes blackface as “a strange mix of envy, fascination, desire, and fear”, the fear being the rejection of Black groups rising up and taking power. He backs the claim that blackface is a form of degradation and oppression, and is not in fact a result of admiration.

Similarly, American abolitionist Frederick Douglass stated that those who participate in blackface are “the filthy scum of white society, who have stolen… a complexion denied to them by nature, in which to make money, and pander to the corrupt taste of their white fellow-citizens” (The North Star, 1848). At its core, executions of blackface were appropriated dances and humor from Black people who were the actual creators. This thievery led to Black people struggling to profit off their own culture when they performed it, and an enforcement of ignorance from the white people around them.

Since then, the detriments of minstrelsy bled into modern entertainment and culture, beginning in the 70s when the idea of “blaxploitation” earned its prominence. At this point in time, Hollywood was no longer hiring white actors to play Black people, but the mockery of these characters remained. These films consisted of token Black characters, who never held a main storyline and were always “playing pimps, prostitutes, street hustlers, drug dealers, and other unsavory types,” as Britannica defines it. Blaxploitation had similar damages to minstrelsy, where it began to affect the way others perceived Black people, referencing these TV displays when forming their opinion. The trend of seeing them as aggressive and slovenly kickstarted once more, also resulting in non-Black people feeling less sympathy for those characters, and generally for Black people in real life.

In the 21st century, instances of blackface and microaggressive media still exist. These executions could be seen as recent as a few years ago in broadcasted media such as the Office, Mary Poppins, and even SNL to name a few. Celebrities like Jack Black, Robert Downey Jr., and Jimmy Kimmel have also been accused of wearing blackface in their respective films, proving that the remnants of minstrelsy still taint Hollywood and the idea of overstepping boundaries when exploring what people find funny.

Though less blatant and vulgar in today’s society, shadows of minstrelsy lurk and persist as a painful reminder of America’s deep-rooted racism and bigotry. To move forward, it must be confronted head-on with education, empathy, and systemic change. Eradicating these forms of racial dehumanization demands collective action and a commitment to rewriting our shared narrative.