We’re never going to have music like we used to. TikTok changed the function, consumption, and perception of music permanently. Every week, a new artist has their 15 minutes—or 15 seconds—before being flushed out into the sea of endless content. It’s hard to compete, and there’s no way of telling if your music will ever be picked up by the next trend. But TikTok also gave a revival to artists that have been around forever and are maybe just being appreciated by the younger generation. Take The Smiths, The Cranberries, Kate Bush… artists that were big throughout the 80s and 90s but didn’t take a strong hold of Gen Z until TikTok. Similarly, singer-songwriter Fiona Apple’s most recent break was not at the hands of releasing a new song or having her music play on television. Her music has been all over TikTok, from “Paper Bag” to “Under the Table,” and a fascinating youth culture has emerged around it.

“I’m a frightened, fickle person / Fightin’, cryin’, kickin’, cursin’” – Better Version of Me

Let it be known that Fiona Apple is not a “new” or “emerging” artist. Winner of 3 Grammys, Apple released her debut album Tidal in 1996 (aged 18), and would release four more albums after that. She took the music world by storm, young and passionate and outspoken. Her vocals were mystic, and her lyrics touched on everything from feminism to a loss of innocence to falling in love.

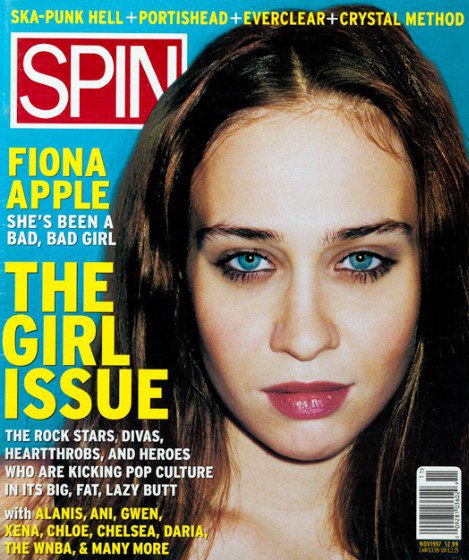

Apple quickly became notorious, though—even today, narratives that Fiona Apple is “crazy,” “erratic,” or “unhealthy,” flood the internet. She’s been heckled at shows, told to “get better,” and accused of being on drugs countless times. When Apple fires back at these remarks, she gets framed by magazines and publications as completely unstable and thus not worth listening to. If she wasn’t insane, she was a “sexy, temperamental teenager” (Spin Magazine), or “the next waif supermodel” (New York Times).

Most of the backlash against Apple comes from the fact that she is a woman who makes bold music and statements according to what she wants and thinks is right. As Apple said herself, “Kick me under the table all you want / I won’t shut up.” The responses were even worse when Apple was younger, as people hardly took her seriously. For artists like her, fighting to be understood and taken seriously may just be a trait of the trade. For all the artists who need time to think between interview responses, who have feelings—private or public—there’s no end to critics using their names just for clicks.

Throughout the height of her career, Apple openly despised the music industry and what it stood for. She was against the idea of pop culture and young people following whatever they thought was cool because it was on TV. She still is, although today she keeps to herself much more and hardly appears on social media, at concerts, or on TV. This belief guided a lot of Apple’s early public appearances and statements. She seemed to be the boldest antithesis to the rest of the self-obsessed, culture-obsessed world.

Apple often writes about rape and sexual assault, having experienced it herself. Her most recent album, Fetch the Bolt Cutters, was especially explicit about this subject. Many people, especially Gen-Z, praised her for her lyrics and decision to sing about such things. Young women and teen girls felt that their feelings and anger against patriarchal violence were finally being put into a digestible form of media.

“Yet another woman to whom I won’t get through” – Ladies

For girls grappling with the crumbling world around them, an artist like Apple presented a sound and relatable voice to fall into. She was brooding and angry at the misogynistic world around her—just like many young women and girls today.

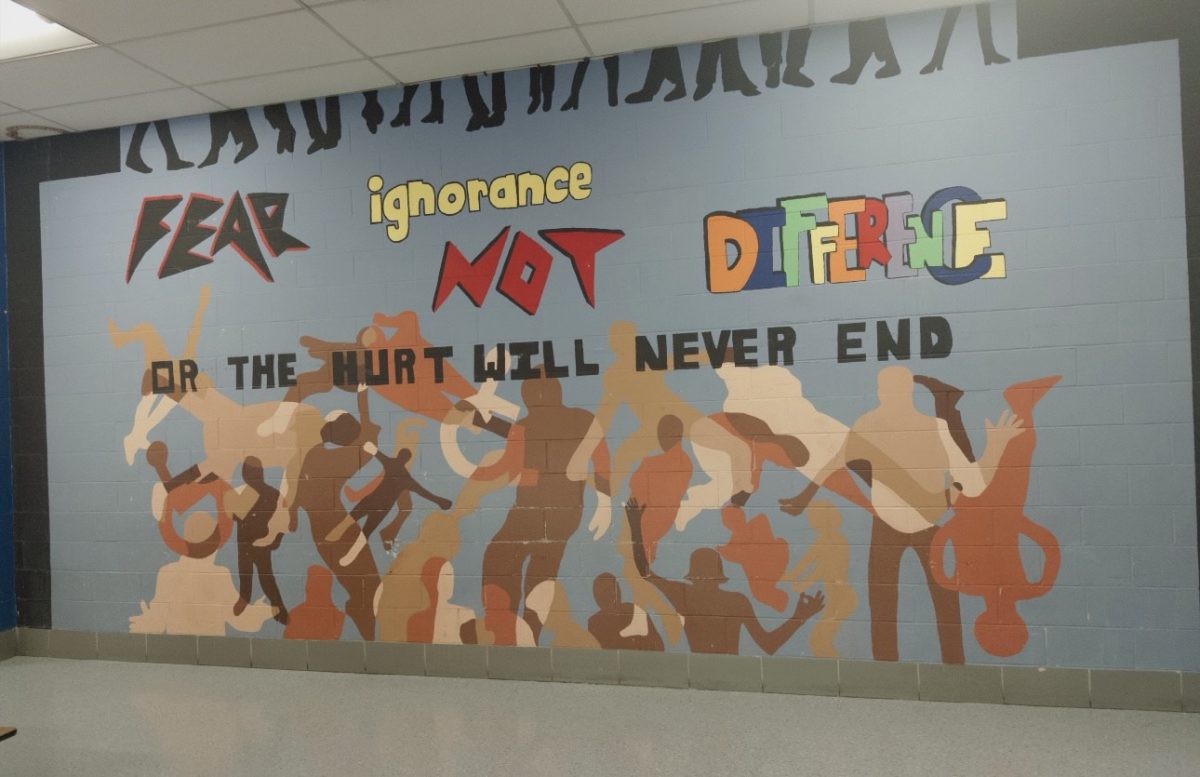

And so was born the phenomenon of “female rage.” Of course, women’s rage is not a new concept, but it has been reborn in a way on TikTok. Essentially, “female rage” was a wave of young women and girls looking at the manifestations of women’s rage in media and romanticizing it. It was beautiful and empowering to be angry; to refuse to sit pretty and accept the misogyny being thrown at you. The uplifting of angry women was also a response to men’s anger being hailed as valiant and masculine, while women were called hysterical and irrational. Fiona Apple was the new patron saint.

The musical culture of Gen-Z is largely curated around the fact that our world is failing in front of us. We are actively trying to cope with our systems either being in ruins or working against us. Thus, musical voices like Apple’s who blatantly resist everything the modern world is are appealing to young people. And of course, Apple seemed to perfectly embody female rage—she had a way of singing that was not pitch perfect and refused to be so.

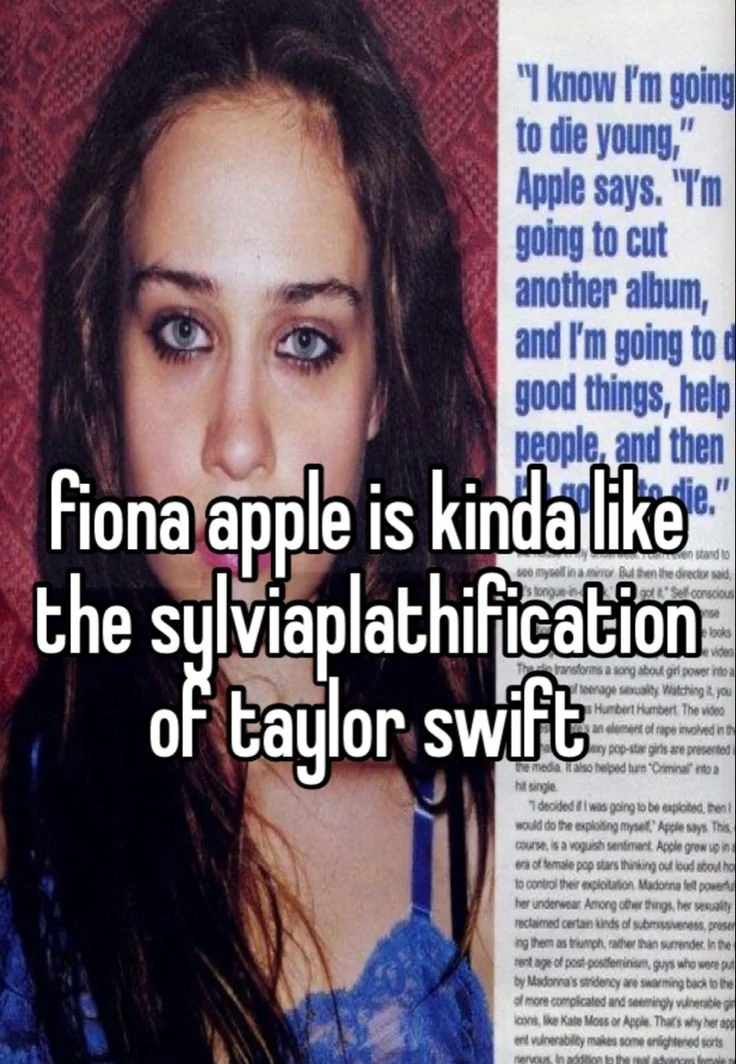

She was particularly liked by “female manipulators”—another phenomenon that arose almost in retaliation to the rise of male manipulator culture. These “female manipulators” characterized themselves around female rage, femininity, resenting men, and most importantly, musicians like Lana Del Rey and Fiona Apple. They consider themselves undateable, unlovable, plagued by mental illness, and yet uber-cool. Whether the manipulation part is genuine or not depends on who you ask. Either way, this was another case of young women trying to cope with the misogyny around them by finally showing their anger and taking out their pain on others, especially men.

When identities emerge inherently based around a piece of media, we as a culture inevitably encounter some issues. People like these “female manipulators” (also called “femcels”) base their entire selves around certain music—or rather, the skewed yet popular interpretation of certain music.

See, as people continued to promote Apple’s music in this way, she became associated with the hyperconsumption of media and rapid-moving vapid trends. Apple had become a vessel for other women’s cynicism for the world. It was exactly everything Fiona Apple did not stand for. She was against this shallow narrative that the music industry was the end-all be-all for young people’s identities, and she was very much against the idea that there was nothing we could do about misogyny and violence. Her newest wave of fans seemed to want to do nothing but sit in their anger—to produce rot, rather than action against the misogyny they observe. An entire new fanbase has been cultivated for her around negative emotions and inaction.

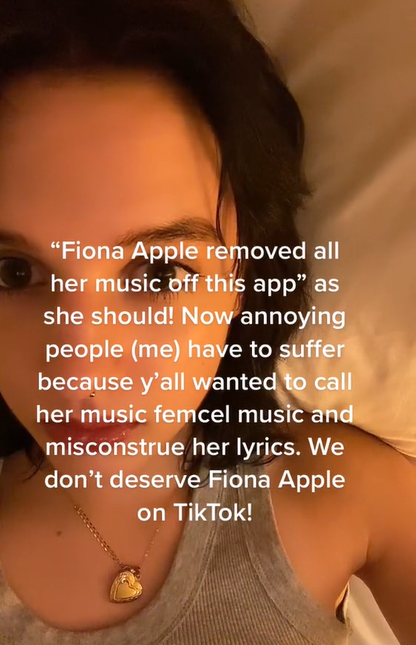

Thus, Fiona Apple removed all but two songs of hers from TikTok in 2022. Though she never released a statement confirming her reasoning, many speculated that it was because she disagreed with how her music was being used. We do know that Sony, who owns Apple’s record label, signed a deal allowing the use of music released under Sony all across TikTok. The removal of Apple’s music was likely a decision of her own.

“‘Cause I don’t appreciate / People who / Don’t appreciate” – Periphery

As discussed, the phenomenon of “female rage” and how it is treated on TikTok ultimately goes against all of Apple’s values. But the issue goes even deeper than just the overconsumption of media.

By treating the concept of women’s rage as special and insinuating that women are differently-wired or exceptionally sensitive, we continue the misogynistic practice of othering. Intentionally or not, we single out women and confirm that women cannot simply be angry. Their anger must be fetishized, turned into a spectacle, and still exist within the realm of femininity. This “female rage” still requires beauty. When we validate the anger of female artists, we do so by calling it beautiful. Womanly. Why can’t anger just be anger?

I wrote about a similar phenomenon in the first issue of Sound Check. Mitski, another female singer-songwriter, has been taken up by Gen-Z as the incarnation of “sad girls.” Young people parade her and her music around as one-dimensional, depressing takes on love and the world around them, throwing out any nuance or other emotion. Just like Apple, Mitski frequently writes about a vast library of emotions, experiences, and ideas, many of which are completely removed from the experience of misogyny or womanhood. Yet, she is misconstrued as a personal diary for every teen girl’s gripes about oppression. In isolation and privacy, there might not be anything wrong with this, but this “reductive” (Mitski’s words) way of looking at women’s art seeps into our view of women artists themselves. We don’t know how to analyze and understand the work of women without considering it a horrific reflection of women’s place in society. Women feel and express the same human existential fears that men do, though, and not everything must be placed in a special category because it’s by or for women. While male artists get to have an entire universe of thoughts that are crucial to the human experience, women can pick between sex and hysteria.

Even if we are opening our arms to female artists who are unabashedly fed up and even a bit repulsive, we still exclude them as long as we treat their anger as something to be sensationalized. When will female artists be allowed to freely express their emotions without it being a spectacle in one way or another? Even when Fiona Apple’s anger isn’t coming from being harmed by misogyny, it is still categorized as different. Other. Ironically, we’ve gone so far into empowering women and trying to normalize their emotions that we’ve just continued to enforce gender roles and exclude women.

Fiona Apple isn’t allowed to be complex. From headlines in the 90s and 2000s to today’s TikTok trends, she’s constantly being watered down to angry and erratic. The reality is, Apple writes about all kinds of things: grappling with monogamy in Cosmonauts, impulsive self-destruction in Daredevil, sensual desire in Hot Knife, persevering with the help of others in Shameika, learning to move forward in her career in Better Version of Me… the list goes on. The inability to separate Apple’s lyrics from her struggles as a woman reflects an inability to see women as complex artists who can write about the same universal feelings that men can have.

In the past few years or so, Apple has relatively fallen off the face of the public sphere—and good for her. Consuming music on such a shallow level at such a rapid pace isn’t good for anyone. Fiona Apple’s sensitivity and depth has been almost entirely lost in the tsunami of new popularity, because, as usual, nuance vanishes the more widespread something gets. We as a culture have a long way to go when it comes to equity and the treatment of women artists. Our women are more than a string of buzzwords, and their music deserves more than a sideways glance and a sad excuse for analysis.

This has been the fifth issue of Sound Check with Jules, the new musical column in the Hatters’ Herald. Tune in weekly to hear about music history, review, recommendations, analysis, culture, and more! To find my favorite Fiona Apple songs, which I listened to while writing, click here.