Parker helps others diagnosed with Kennedy’s Disease

Physics teacher diagnosed with disease in 2006

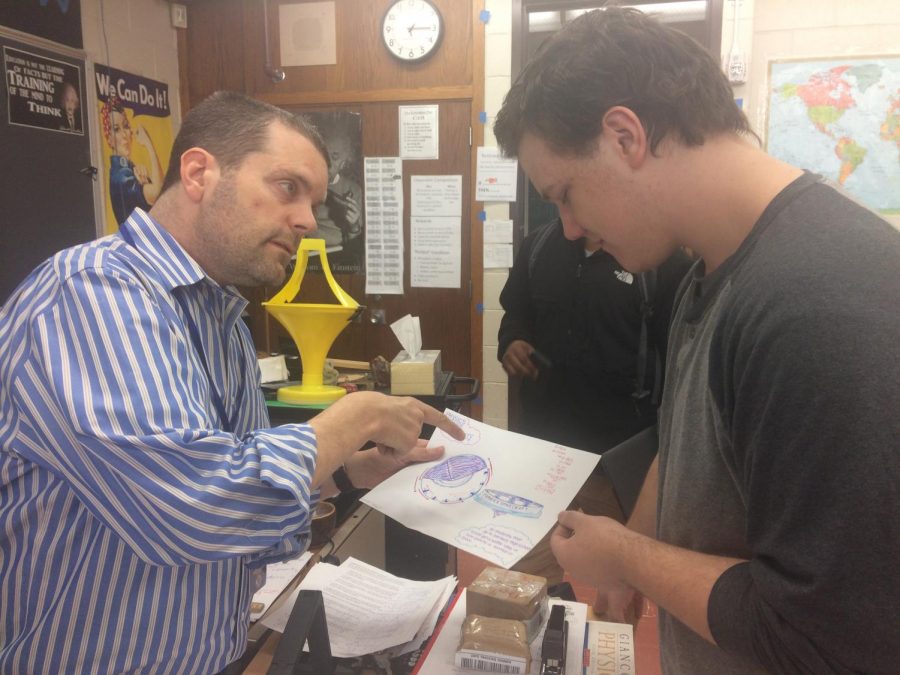

Physics teacher Jameson Parker works on a physics problem with Trevor Roos. Parker is up front with his students about Kennedy’s Disease and how it affects him.

January 26, 2018

After being diagnosed with Kennedy’s Disease in 2006, physics teacher Jameson Parker has not let the condition define him as he continues to help others who have been diagnosed.

According to the Kennedy’s Disease Association, the affliction is a degenerative genetic neuromuscular disease. It primarily affects men, though females can be carriers and experience symptoms. Primary effects include muscle weakness and disarticulations, tremors, and speech and swallowing difficulties. It is commonly misdiagnosed as Lou Gehrig’s Disease (ALS) due to similar symptoms, but unlike ALS, it is not fatal.

In Parker’s family, it was his cousin who was the first to be diagnosed. “When I saw the symptoms that are involved with Kennedy’s Disease, I knew pretty much without getting tested,” Parker said as he recalled hearing about his cousin’s diagnosis. “I knew that I had it. Still, it didn’t really sink in though until I got the official DNA test and was diagnosed.”

He was in his early 30’s when diagnosed. Currently, there is no medically approved treatment or cure for Kennedy’s Disease. Some people participate in physical therapy or in moderate exercise, with some reporting positive effects.

Parker said the symptoms prevent him from being as handy around the house as he used to be, but his wife Heidi has taken on more of that responsibility or they will hire a handyman. Sometimes it also impacts his time with his three sons, Brian, Trey and Ryden. “I can’t go out there and run with my boys,” he said. “I can’t throw a ball around or go camping with them.”

He says this only because he’s asked about limitations; he would much rather focus on the things he can do.

“I have no desire that people feel sorry for me,” Parker says. “In my own life, I prefer to focus on what I can do rather than what I can’t do. And there are still many things I can do with my boys. We spend our time playing games, and building Legos is a popular activity in our house. I also like to do home science experiments with them, such as we recently built a vortex fountain together.”

Outdoors, he hooks up a cart to the garden-tractor and he tools around with Heidi and the boys piled into the cart and in tow.

Besides the comfort he draws from his family, Parker also derives strength from his Christian faith. “It is a central part of who I am. Though I am a science teacher, I believe that there is more to this life that what we can see and measure.

“My relationship with God is very important to me and is a great source of strength in my life,” he continues. “My faith has led me through major decisions in my life such as leaving a job as an engineer to become a teacher and adopting our three boys. We also have great friends in our church family, people on whom we can call for help.”

He has also found strength in the people he meets at the annual Kennedy’s Disease Association Conference that he and his family attend every year. At the fall conference in Washington, D.C., Parker and others diagnosed with the disease listened to presentations on the latest research. Parker is also a board member of the association, which has awarded more than $1 million in research grants to help find a cure or treatment.

Attending the conference helped when Parker was first diagnosed, since he saw how people “still were engaged and doing things, and that made me realize that just because I had this disease didn’t mean that my life was over.”

One of the things he looks most forward to each year at the conference is helping people who are newly diagnosed. He hopes to be an example of perseverance when he talks about it: “I say, ‘Yes, it stinks; you’re going to have to make adjustments. It’s difficult, but you can still live a full life.'”

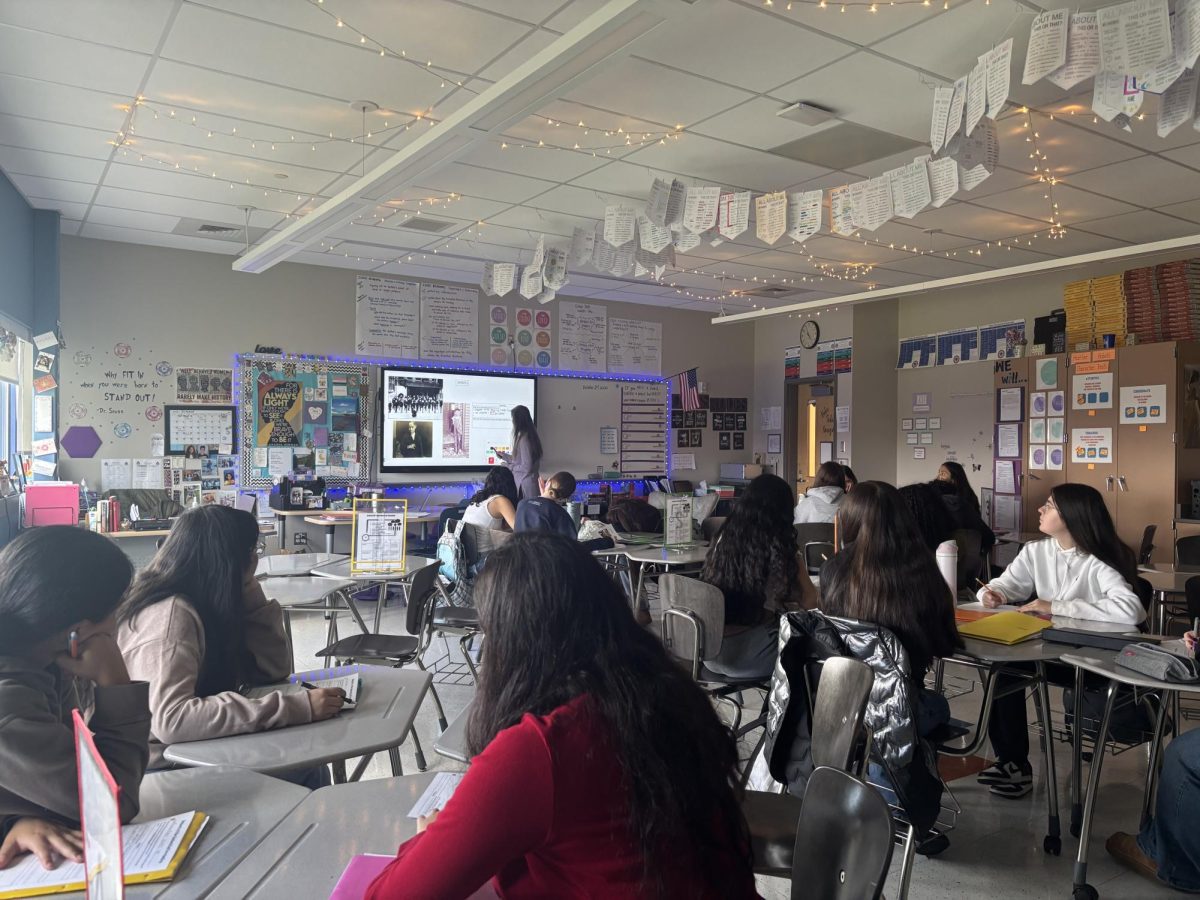

He makes similar points to his students so that they understand why he gets around his room and the hallways in a motorized scooter, or why they may see him using canes to walk. He adds some days are better than others, and that factors into which aid to use.

One effect of Kennedy’s Disease is deteriorating speech. Knowing this, Parker said he was worried that it would affect his teaching abilities. But junior Trevor Roos emphasizes how the disease doesn’t seem to affect Parker’s teaching.

“He still strives to make each one of his students succeed to the best of their ability,” Roos says. “He still makes class enjoyable and something I look forward to.”

Some students are surprised that Parker opens up so freely about Kennedy’s Disease. On the first day of each school year, he explains to his students that he has the disease. He wants people he comes in contact with to be aware and understand what he has and is open to talking about it. On the outside of his classroom door, he has posted an explanation of the disease.

“He seems comfortable talking about it,” junior Nathany Deoliveira says, “and his experience with others.”

Although Parker has had to make adjustments in the classroom he emphasizes that his love for teaching remains. He is constantly motivated to continue, saying, “I love the diversity here, I love the students, and I love the teachers and administration. So being in such a great environment motivates me.”

In addition to teaching, representing the association, and being active in his church, Parker is also adviser and coach to the school’s winning chess team. Before becoming a teacher, he worked in the industries of space science and alternative energies.

Always the teacher, and always the life-long learner, Parker reflects on what he has learned about life and people since his diagnosis.

“I have learned it is good to accept the help of others,” Parker says. “Sometimes we just can’t endure — not alone, we need others.

“Because of this disease, I have seen again and again that people are happy to help me with things I can’t do,” he continues. “We are not intended to go it alone. We all need a helping hand sometimes, and that is a good thing.”

Jameson Parker enjoys taking the family — his wife, Heidi, and their three sons, Brian, Trey and Ryden — for rides around the yard.

Lucas Amaral • Mar 15, 2018 at 8:31 pm

Great Job Elizabeth,

I can see that the disease can be quite the battle and am glad you publicised Mr. Parkers story for a better universal understanding and awareness of it. Cant wait to read your next story!

Buzz Hägglund • Feb 10, 2018 at 11:56 pm

Good story very well written. Greetings from Saskatchewan Canada.

I noticed symptoms of K.D about fifteen years ago and was diagnosed in 2010.

I have weakness in my arms, legs, but mostly my jaws are weak. Life is still very much worth living and if K.D is going to take me down it’s going to have to keep up as I have stuff to do and

I don’t give up easily. I have great faith I our Creator and I draw much strength from that.

Always appreciate hearing from others with this disease as I don’t feel so alone.

Peace and blessings to you all

Bz…………..

Xavier Alvarez • Feb 3, 2018 at 6:07 am

I was diagnosed Kennedy’s disease one month ago

I am Ecuadorian

We must continue enjoying our life and the things that we love

Thank you for the message

Xavier

Eugene gillies • Jan 31, 2018 at 5:54 am

Hi jameson

Very well written piece, i have been diagnosed in 2011 after a couple of years wondering whats up!!

Keeping positive is the most important thing to do’

I had to give up a lot like garden fishing hill walking and a lot more! But hey!! Im here enjoying life!!

My saying is “embrace what you have, not what you have not””

Keep up the good work!

Eugene

Dublin . Ireland

Graham Lee. • Jan 25, 2018 at 4:16 pm

An excellent article all round. I have had KD for 16 years and truly understand the need for a positive outlook. I live in Northern England. There are great strides being undertaken over here, particularly in the last 5 years. My best to everyone – Graham.

Paul Lazenby • Jan 24, 2018 at 11:32 pm

What a pleasure to read your excellent article on Jameson. As a fellow sufferer of Kennedy’s Disease in Canada, I have had the privilege of meeting him at conferences in both San Diego and Alexandria. Sometimes its harder to stand tall than people realize, Jameson does it anyway and it brings out the best in us all.

Marcia Parker • Jan 23, 2018 at 7:34 pm

Thank you for your well written and inspirational article about Jameson. We think he’s pretty special too.