Dreamers express dismay over Trump’s DACA policy

Demonstrators march in September in Los Angeles after President Trump announced through Twitter his DACA policy.

October 13, 2017

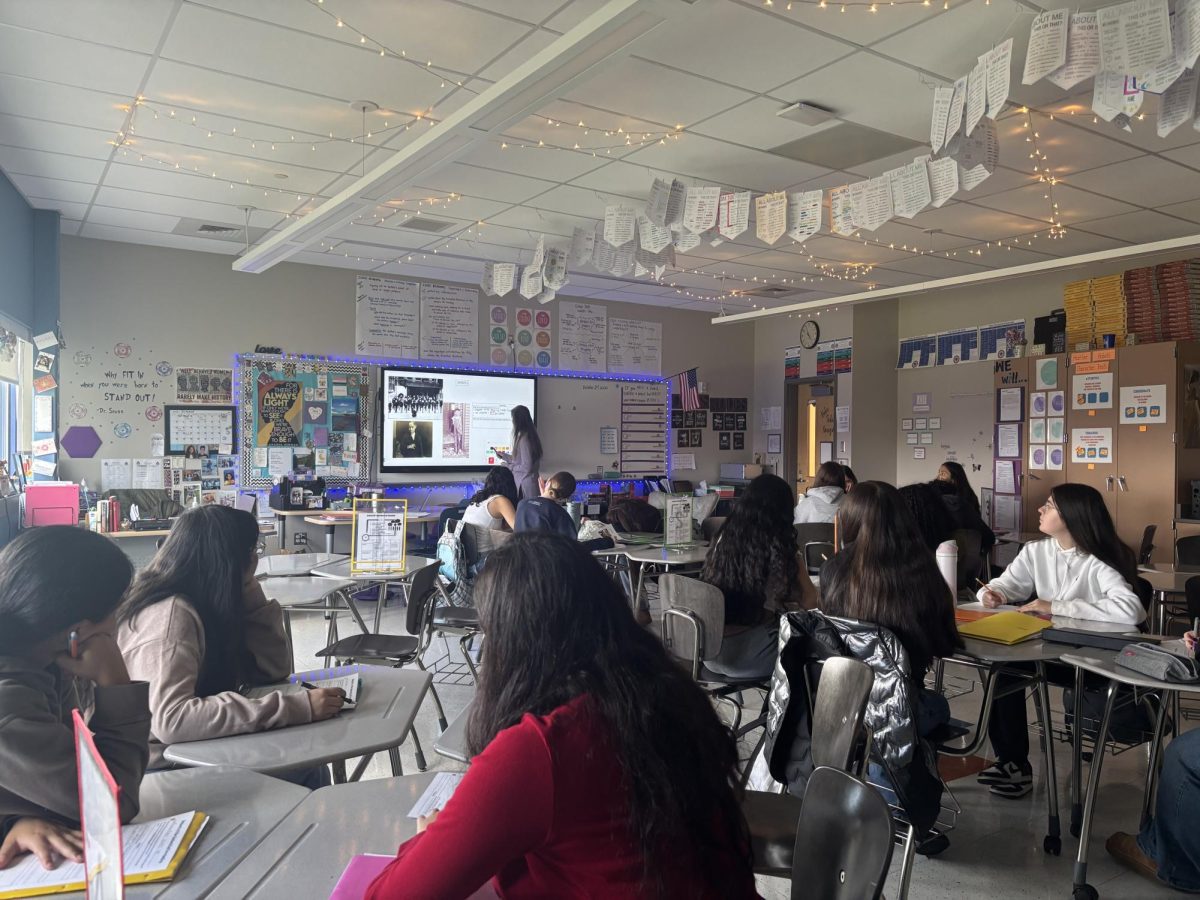

Like many other undocumented immigrants across the country with status, students here are trying to figure out what lies in store for them as the Trump administration and Congress figure out their stance on the issue.

Donald Trump announced that DACA ended as of Sept. 5, but that there would be a six-month delay to allow for the Department of Homeland Security to make formal judgments on current beneficiaries whose papers, accepted before Oct. 5, expire between Sept. 5 and March 5.

As of now, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services will not consider individuals for DACA protection who did not submit an application by Sept. 5.

DACA has protected 800,000 young undocumented immigrants from deportation and provided a work permit ever since its commencement in 2012 as stated by U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. The program delays deportation for up to two years with the deliberation of renewal.

Consideration for renewal is granted as long as the recipients meet several guidelines, such as being enrolled in school and no criminal record. Even if the recipient has graduated or is over 31 years of age they will still be assessed due to the fact that as an initial DACA beneficiary you cannot age out of the program as

Trump has sent mixed signals of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, a program established in 2012 by President Obama to allow undocumented immigrants who are working and in school to stay in the country for a certain period without fear of deportation.

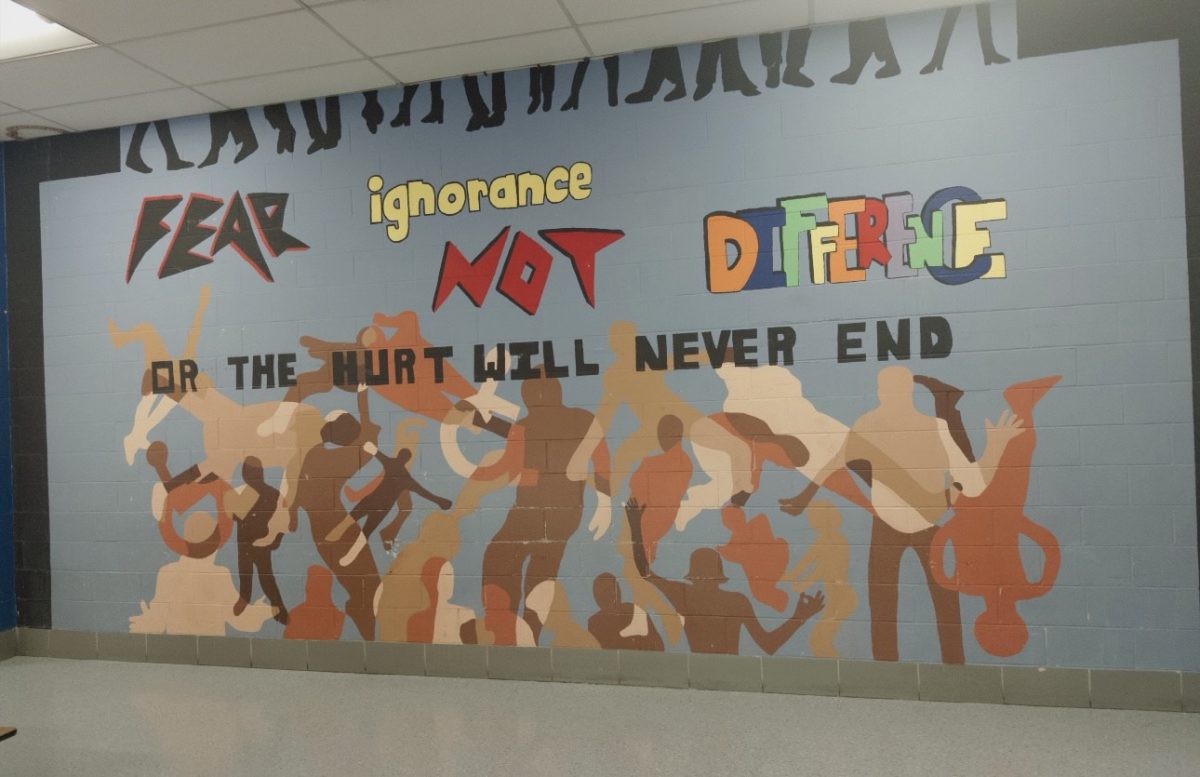

Several of these young immigrants, referred to as “Dreamers,” came to the United States at such a young age that they have little to no memory of their birthplace; nevertheless, they have a deep connection to where they have been raised in the states.

This includes Danbury High School alumni Angie Tovar, an active DACA recipient who attends Western Connecticut State University and is enrolled in the Honors Program maintaining a 3.9 GPA with a total of 19 credits.

Tovar and her family entered the U.S. in 2003 due to the hardships her family endured from her father’s unemployment in Colombia.

Tovar explains the disconnect. “I’m not from here and I’m not from Colombia, I’m stuck in the middle. I don’t feel like I’m from here, because I’m not accepted here, and I’m not from Columbia because I haven’t been there since I was 5.”

The Obama administration has given approximately 689,800 active DACA recipients the feeling of security. “DACA was the first time I actually felt a little accepted in the country,” Tovar says.

Tovar balances school, two jobs, and the stress of having her residency status in jeopardy while having to pay her way through college without receiving any financial aid.

She recalls the moments of her difficult college application process. “During my senior year of high school, I would cry so often because I was like, ‘I’m not going to be able to go to school.’ I didn’t see a way. [My parents] are not able to pay for college for my sister and me, everything has to come out of our pockets, and they feel bad about that.”

Before the initiation of DACA, undocumented individuals could not obtain a driver’s license or a work permit. “It gave me the opportunity to start saving up so that I could afford to go to college,” says Tovar.

Tovar had fears that her dream would never come true, but with the opportunities of DACA, “It made the process easier.”

Tovar elaborated on the moments she has witnessed different outcomes for some individuals. “I’ve seen it happen to people when they don’t have a Social Security number. It’s so much more trouble, people are not informed on how things work, and are told they can’t do it. Most of the time it’s not true, they’re just not informed on how it is.”

Senior Nelson Neira who had testified before state lawmakers for equal access to financial aid disclosed his disappointment, “I felt really bad because the organization that I work on, worked and helped to pass DACA as a law. It was a work of 5 years… It was a long fight that for DACA and it ended really fast.”

Tovar expresses her dismay that DACA may come to end as well as the ambiguity that will come afterward, “It’s really unfair. When it’s like okay what are we supposed to do? We’re supposed to go back to a country we don’t know, we’re supposed to go back to being dirt poor and leave everything behind?”

The future of DACA is now in the hands of Congress. Donald Trump is saying he will support DACA on the condition that Democrats support his idea of building a massive wall along the country’s southern border.